Reprinted from…

Why Young Men Are Bored and Angry

By Robert Murphy, Aesthetic Realism Consultant

As the school year is under way, parents, teachers, and students are terrified of the anger that erupted last year in the school shooting which caused the deaths of children and one teacher.

I know—and I feel this with the depths of my being—that the scientific, terrifically kind education of Aesthetic Realism, founded in 1941 by Eli Siegel, can have the out-of-control anger in young people that caused these tragic deaths end. I make this statement carefully, after over twenty-five years as an Aesthetic Realism consultant teaching young men between the ages of ten to twenty-one, with my colleagues.

Aesthetic Realism makes clear the beginning fight in the mind of persons of any age, between wanting to like the world, see meaning in it, which is the deepest desire of all of us, and the hope to find the world a contemptible mess and so feel superior to everything. Aesthetic Realism defines contempt as “the addition to self through the lessening of something else.” Contempt is everyday and ordinary: simply not listening or pretending not to—as a boy of twelve finally responds to his mother’s repeated calls to dinner, “Oh, I didn’t hear you.” Contempt is also the cause of feeling that just because we are different from a person of another race, we are better, and therefore can do as we please with that person.

It was the accumulation of everyday contempt that had young boys feel as they looked down the barrel of a rifle that they had the right to shoot other children. It is a national emergency that the fight between contempt and respect be studied in schools, talked of in homes, and seen as a priority in government offices. The sanity and kindness our great country is looking for is in Aesthetic Realism.

Early Boredom, Early Anger

By the time I was sixteen, I felt that if I lived another twenty years on this planet, it would be long enough. I did not see the world as exciting, so I had to make it exciting by stealing cars, racing motorcycles, taking drugs. When I met Aesthetic Realism at the age of twenty-four, I began to learn that the world as I saw it was completely different from the way the world is. I was amazed to learn that the world has a logical structure which, when known, can honestly, with all the facts present, be liked.

When I first read this principle of Aesthetic Realism by Eli Siegel, “The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites,” I thought, if this is true, this is the greatest discovery of mankind. Twenty-nine years later, I am sure it is true, I am sure it is the greatest discovery of mankind, and I am glad I am alive to study this philosophy and teach it to others.

Contempt versus Liking the World

In an Aesthetic Realism class, Mr. Siegel told me, “Anybody who doesn’t think that contempt is a continuous study, living study, and doesn’t want to know all about it, is a person who wants to be hurt and miserable.”

Aesthetic Realism says dogmatically that young people are in anguish because they feel they are in a world that they cannot like. Part of this is an unjust economic system which permits young people to be jobless, and to lack education because the cost of college is exorbitant. Many young people are both jobless and homeless.

Yet, I learned from Aesthetic Realism, we have a choice about how to use what we meet: either to know, and to fight for justice; or to see the world as a contemptible place, a fraud. The second is easier and more popular but makes a young man dangerous to others and to himself. What this does to a person was seen and described by Mr. Siegel: “For anyone to say, I’m not interested and don’t intend to be interested, that person is making for himself a private graveyard even while he’s alive.”

Aesthetic Realism Consultations

In studying Aesthetic Realism, my way of seeing the world changed. I once hated books, thought all people were phonies, and that art was off the mainstream of life. The very things I saw as meaningless, I came to see, were the things that could answer the deepest questions of my life.

I tell now of the consultations of Don Morgan, a sixteen-year-old high school junior. He had come to feel the world was not worthy of his interest and was definitely boring. Yet he was pained by this feeling. He said in one consultation, “Lately I feel like I haven’t been doing anything, like I haven’t been going out, and I don’t know why.”

Many young men make themselves important by seeing the world as a mess, a domestic mess, an economic mess, a political mess; they can see things as ugly, dirty, bad smelling, ill-proportioned. Wars continue; death and terror are staple items in every newscast and TV drama.

A young man decides the world is meaningless and he has a right to be superior and have contempt for it, and the result is always that he is depressed or against himself in some way. This is the logic Aesthetic Realism presents for the first time. Every young man should be studying Aesthetic Realism. People should be hearing Aesthetic Realism on the news, in schools.

The Young Mind asked Don Morgan, “It’s not a good thing to feel bored, but in your mind is the pain of boredom better than the pain of getting mixed up with humanity?”

He answered, “I don’t know.”

TYM. The conflict you have—and other people have it too—is, can people really add to you or do they take away from you? For instance, do you think someone who lived three hundred years ago could add to you?

DM. In what way?

TYM. Make you more yourself. Would you be glad if that could happen?

DM. Yeah, sure.

TYM. So we should enlist the aid of this person who lived three hundred years ago. His name is Rembrandt. Do you know his work?

DM. Not really.

TYM. Are you interested?

DM. Yeah. I guess so. I’m not sure.

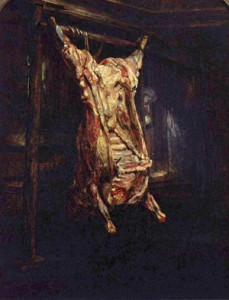

We looked at Rembrandt’s The Slaughtered Ox and asked Don Morgan to describe it.

He said, “A dead ox hanging up on a pole, held up by ropes. The colors are different: red, black, light brown….”

He said, “A dead ox hanging up on a pole, held up by ropes. The colors are different: red, black, light brown….”

We asked, “Do you think this made for an emotion in Rembrandt? There could have been a lot of pretty things he might have painted. Do you think there is anything beautiful about this painting?”

Don Morgan answered, “Yes. The way he presents it. It looks light.”

We wanted Mr. Morgan to see that the world around him, however messy and senseless it might seem, had form. We were teaching him the Aesthetic Realism principle: “The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites.”

In Aesthetic Realism: We Have Been There, consultant Dorothy Koppelman writes of The Slaughtered Ox:

The permanent opposites of the world are here in the thrusting forward of the dead ox and in the hidden figure of a woman. Assertion and retreat are motions of reality and they are in us …. The painful, lumbering, awkward quality of the slaughtered ox is redeemed by the pride with which it is lifted and put forward into the light.

Among the many questions we asked Don Morgan were these: “Did you betray something narrow in yourself when you found this painting interesting?”

“Yes.”

“Is that a defeat or a victory for you?”

“A victory …. I felt happier looking at the picture.”

“Is there anything in the world that could not add to you? Tomorrow when you are home you are going to have to make a choice: Don Morgan plus world or Don Morgan minus world. The more that is added to you, do you feel heavier or lighter?”

“Lighter,” Don Morgan said.

It is not too much to say that this consultation saved Mr. Morgan’s life. He said he was different from that day on, and we have seen that ourselves. Mr. Morgan no longer sits hour after hour staring into the television set. He has joined the baseball team, is interested in what is occurring in the world, and has for the first time become interested in talking to a girl.

Aesthetic Realism is the means of changing boredom and anger, by changing one’s state of mind from contempt to respect.

For information, including about consultations via video conference, you can contact the not-for-profit Aesthetic Realism Foundation, which is at 141 Greene Street, New York, NY 10012, 212.777.4490.

From the January 7, 1999 San Antonio Register