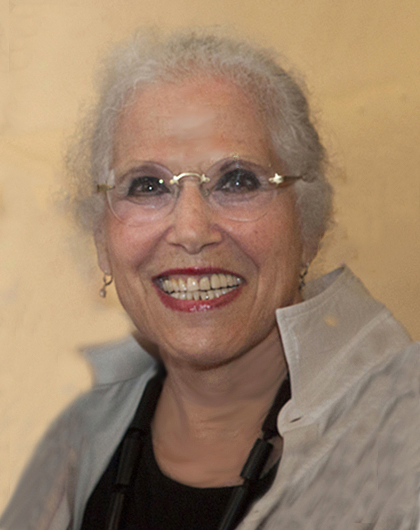

Ruth Oron, born in Israel, is an essayist, sculptor, and Aesthetic Realism associate. She writes:

People everywhere are troubled by their inability to give deep attention to things outside themselves. In his great lecture Mind and Attention, Eli Siegel provides the explanation of what true attention is, and why people have difficulty giving it.

For so much of my early life I was definitely interested in getting attention but not too interested in giving it. My desire to feel I was better than other people ran ahead of my desire to learn, to see meaning in people and things. Though I cared for swimming and long-distance running, and liked to crochet and knit, as time went on I found it more difficult to give steady attention to the world around me. Increasingly I had a hard time reading, and paying attention when someone else was talking.

The greatest thing happened to me when I began to study Aesthetic Realism in consultations, classes, and public seminars, and learned about the fight in every person between liking the world and having contempt for it. These two desires are central in understanding attention, as editor Ellen Reiss describes richly in the commentary preceding this lecture, published in the issue of The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known titled “Attention and America.”

Studying Aesthetic Realism changed my life—and the change happily continues! I learned what giving attention really means, and how beautiful and exciting it is. I learned that to give attention truly, is the same as taking care of myself, and I saw that it makes me much larger, deeper, more truly me. My desire and ability to give attention to things, books, and people came alive!

Mr. Siegel’s comprehension of humanity is exemplified magnificently in this lecture, which I passionately recommend people study.

In her commentary Ms. Reiss writes:

We begin to serialize Mind and Attention, by Eli Siegel. He gave this great lecture in 1949. And in it, that subject attention—so wonderful yet often so distressing to people—is understood truly, with Mr. Siegel’s beautiful kindness, depth, scope, and also humor. He explains the deep mix-up: how we are, without knowing it, both for and against the giving of attention, and the getting of it. Later in the lecture, he will explain something that psychiatry is still massively ignorant about: what in a person interferes with his or her giving attention. I anticipate that discussion by saying: Mr. Siegel has shown that the big thing hampering the ability to give attention is contempt for the world.

He showed—and there is nothing more important in the understanding of mind—that contempt, “the lessening of what is different from oneself as a means of self-increase as one sees it,” is the cause of all cruelty. And having contempt is also that which weakens our mind. The chief reason we don’t give attention is the feeling within us that outside things don’t deserve it. A seeming inability to be attentive is both a result and form of contempt for a world we see as unworthy of our thought.

Meanwhile, the magnificent fact that our minds were made to give attention to the world—to its objects, colors, sounds, knowledge, to the feelings of other people—is evidence for something else Eli Siegel was the person to explain: “Man’s deepest desire, his largest desire, is to like the world on an honest or accurate basis” (Self and World, p. 1).

Read the issue of The Right Of in which this lecture begins.

Read the other issues of The Right Of in which this lecture is serialized.