Mind and Intelligence, Part 2

By Eli Siegel

The Agonizing Problem

We cannot divide intelligence. If a person says, The way I’m intelligent about my secret life is different from the way I’m intelligent about going to the store to buy some clothes, he is going to get into trouble. This can happen in ever so many ways. For example, in proverbs we see a good deal of keenness, awareness; then, there is another kind of awareness that is separate. I read from a book published in the 1850s, Polyglot Pocket-Book [comp. J. Strause], which contains many languages.

Take a proverb, intelligent, but not having the whole story: “A hungry belly has no ears”; “Ventre affame n’a pas d’oreilles.” When we are physically ill at ease we cannot listen. But it is also true that because we don’t want to listen, we can be physically ill at ease. The very nature of intelligence is to accept the notion of contradiction. A man can be against his wife because he is so much for her: he wants her to be so good that he can’t stand her being in any way incomplete, and therefore is mean on that point. All kinds of things that to the ordinary way of looking seem silly, are really the most emergency problems of self.

“Nothing venture, nothing have.” That means you should be bold. Then, there are a good many proverbs that tell how careful you must be: “Look before you leap.” So, how can you be bold and careful? “Hunger is the best cook”; “There is no sauce like appetite”: what is not recognized is that there can be a tremendous appetite because you’re not hungry; that is, sometimes you want to conquer food in order to show that you can despise it.

After learning that “God helps those who help themselves,” we have this proverb: “He was born with a silver spoon in his mouth.” One of the things that intelligence hasn’t done, the ordinary intelligence, is put together luck and effort.

People, in order to be intelligent, have to be original; every girl wants to have a dress that looks different, and at the same time wants to be like other people. We have this proverb: “In Rome, to do as Rome does”—which means you would have to be fascist in certain years.

We had proverbs about taking care of yourself; but—”Give every one his due.” There are two things in intelligence: to take care of yourself; to care for other people in a true way. The big problem of intelligence is how to feather your nest and yet not spoil the nests of others. That is the agonizing problem, because both correspond to instincts; and intelligence, from one point of view, is only the accurate honoring of instinct. From a deep point of view, intelligence can be called the accurate realization of the complete unconscious.

A Puzzling Symphony

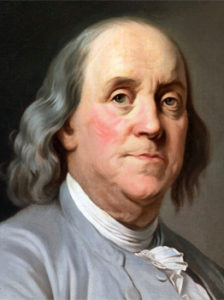

Benjamin Franklin

One of the most intelligent persons who ever lived was Benjamin Franklin. He began the go-getting business in 1758 with his Way to Wealth, in which we have such phrases as “Early to bed, and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.” He is the one, really, who originated the desk memo: those little counsels that make you get orders quickly. Yet in him, with all this earthiness, is a sense of courage, even sometimes a sense of something beyond, which is remarkable. He showed a contrariness about his life with women. He wrote something that was a scandal in the twenties (it was reprinted then)—on how to choose a good mistress; and at the same time, he was looked upon as a paragon for the youth of America. I’ll read some statements of Franklin as an intelligent person [from Familiar Short Sayings of Great Men, ed. S.A. Bent, 1910]. He was born in 1706 and died in 1790, and he kept busy for a long, long time.

“‘I think, father, if you were to say grace over the whole barrel, once for all, it would be a vast saving of time.’ A suggestion that Franklin made at the age of twelve, when the winter’s provisions had been laid in, and he thought his father’s daily grace rather long.” This shows that Franklin had his feet on the ground; and that kind of intelligence is important. Aesthetic Realism stands for the intelligence that can look at a button with interest; if need be, deliver a lecture on a shoelace. Any person who has a contempt for buttons will have a contempt for God. Buttons and love are of the same world. He who can get passionate about buttons or shoelaces has a better chance in the field of true love.

Take another statement of Franklin: “Those who would give up essential liberty for the sake of a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety.” This man who was such a practical person, his eyes on the ledger constantly—this person is now getting to be ethical, courageously idealistic and sharp.

“Those who would give up essential liberty”: one of the things we have to understand is how we are impelled to do unintelligent things. I have been in a position to tell many persons that something in them thinks that what seems outwardly stupid, silly, absurd, is the height of intelligence. For example, when a person tells me, “I went to my relatives’ and I couldn’t say a word to any of my relatives. I was struck dumb. I felt awful. I didn’t listen. What happened to me?”—I try to say, “You wanted to show those relatives they couldn’t affect you: something was working without your knowing it that was being ‘intelligent’ all over the place.” If we’re two people, what can be smart for one person can be very dumb for the other.

From one point of view, we want to be generous; from another, we are always ready to think we’re a sucker. Much agony can come from that. The only way to be intelligent, therefore, is so to see ourselves that the thing that makes us prudent, cautious, reluctant, seems to come from the same person as that which makes us generous, courageous, forgiving.

In this statement, Franklin is no longer the candle-measuring person, the sugar-weighing person. He is saying that liberty is also part of intelligence. That can make one understand how a child can go hungry rather than give in to an unconscious loss of principle, why women can be unhappy in order to maintain a certain notion of their individuality, their liberty. If we are going to be intelligent only about the things we seem to want, we’ll be stupid, because we don’t know what we want. There are forces in us that are tremendous that we don’t know about. The psychoanalysts have muddled those forces. The sexual happens to be a phase of something larger. If we cannot take these forces into account clearly, how can we do an intelligent job with our whole selves?

Many people have been surprised when suddenly they find themselves paying the checks of everybody at the table. Later they think they’re dopes, but they had to do it. They don’t know that something in them is making them more generous because elsewhere they have been less generous than they wanted to be. We have to see that the selves we have to take care of can be in a delicate and dark civil war. It is a puzzling symphony, and we cannot just say, “Symphony, go ahead—become a flute.” It won’t. We have various purposes at one time, and if we cannot put the purposes together, one purpose will be used against the other. And that is not such good intelligence.