Marion Fennell, singer with the Aesthetic Realism Theatre Company, writes:

I think this article by artist and Aesthetic Realism consultant Marcia Rackow is wonderful. In it, she writes about the great 20th-century sculptor Alexander Calder and the surprising and thrilling way heaviness and lightness are present in his work. She shows vividly not only why Calder’s work is beautiful, but also how we can learn from it about our very selves. The basis of Ms. Rackow’s article is this fundamental principle of Aesthetic Realism, stated by Eli Siegel: “All beauty is the making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

Heaviness and lightness are opposites that have confused and troubled people, including me. For example, in the past, I would go out with friends and be very lightsome, laughing a lot (mostly at others); and the next day, would lie on the couch like a slab of stone, not caring to do a thing. I’m so grateful to be learning how to see the world and people with respect, how to be increasingly fair to them. As a result, opposites like heaviness and lightness are so much better related in me: I no longer feel bored or stuck, and now when I’m excited, even exhilarated, I feel my feet are firmly on the ground. Studying Aesthetic Realism has given me the very happy life I so longed for!

Marcia Rackow’s article begins:

“The first time I saw Alexander Calder’s Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, I loved it! I was seven, and my parents had taken me to the Museum of Modern Art. The mobile hung from the ceiling above the stairwell, all the parts were turning ever so slowly in the air, and I thought it was wonderful!

Then, in the garden I saw his Whale. It was all black and sitting on the ground, but it seemed light and joyful.

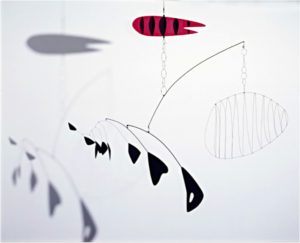

One of the most popular artists of the 20th century, Alexander Calder revolutionized sculpture, added a new dimension to it—motion! He was, said Eli Siegel in his great lecture on sculpture, Weight As Lightness, ‘[one of] the people who just play topsy-turvy with the older notions of sculpture.’ His mobiles were a new art form—

—and his monumental stabiles, which are stationary—

—have enlivened public spaces all over the world. Throughout his long career, Calder’s work extended into many fields: wood and wire sculpture, jewelry, household utensils, toys. He painted in gouache; designed book illustrations, tapestries, an acoustic ceiling, the sets and costumes for a ballet. He even painted a car and planes.

‘Very few works of art,’ wrote his friend, the critic Jean Lipman, ‘can make us feel light-hearted the way Sandy Calder’s do.’ The reason is deep, and is explained by this landmark principle of Aesthetic Realism: ‘All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.’ Calder’s work puts together joy and depth, lightness and heaviness in a way that makes for what people everywhere are yearning for.” >>Read more