Aesthetic Realism Foundation

141 Greene Street

![]() New York, NY 10012

New York, NY 10012

Autumn 2021

Dear Friend,

I am Len Bernstein, photographer and Aesthetic Realism Associate. And I am very proud, at this intense time in America and the world, to write to you about what I consider the greatest institute of learning, culture, and kindness—the not-for-profit Aesthetic Realism Foundation.

Len Bernstein’s photographs are in museum collections and libraries, including the historic Bibliothèque Nationale de France. He has taught and given talks on photography from the point of view of Aesthetic Realism, both in the US and abroad. He is the author of many articles and the groundbreaking book Photography, Life, and the Opposites.

Aesthetic Realism, the philosophy founded by the American educator, critic, and poet Eli Siegel, is based on this landmark principle: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” Here, in my careful opinion, is the criterion for beauty and the basis for understanding ourselves that centuries of artists, philosophers, and people in all walks of life have thirsted for.

Further, Aesthetic Realism explains that there is a fight going on in every person. This fight is between two desires we all have. Our deepest desire is to respect what is not ourselves; it is the desire “to like the world on an honest or accurate basis.” From that desire in humanity come all art, intelligence, and kindness. But we have another desire, which is responsible for every injustice, from snobbish aloofness to racism in all its ugliness. It’s the desire for contempt, defined by Mr. Siegel as “a false importance or glory from the lessening of things not oneself. ” Along with the other cruelties it causes, contempt is the basis of an economy that sees people not in terms of justice but in terms of profit, and deprives millions of what they need and deserve, including healthcare, sufficient food, and a home to live in.

Education: Exciting, Kind, & True

The principles I have outlined very swiftly here are central to every aspect of the enormously diverse, exciting, and so needed knowledge presented by the Aesthetic Realism Foundation. That knowledge is being presented now through video conferencing, across America and beyond. And soon, I hope, it will resume being presented in person in the Foundation’s SoHo building, when the pandemic has ended.

There are classes, which are the height of culture and practicality—classes in, for example, poetry, the visual arts, anthropology, music, marriage, film, and the magnificent Aesthetic Realism Teaching Method. There are monthly public seminars about how the deep and immediate questions of people’s lives are aesthetic questions, answered in the art of the world. There are the Foundation’s great musical and dramatic presentations; and there are the events that are part of the Foundation’s widely respected and popular Outreach Program. (You can read more about all these in the Foundation’s Mission Statement and throughout its website.)

There is the international periodical The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known (TRO), edited by Ellen Reiss. She is the Chairman of Education and teaches the professional classes for consultants and associates I am privileged to attend. TRO contains (for example) serializations of Eli Siegel’s lectures, poems and essays by him, as well as groundbreaking articles by people who study and teach Aesthetic Realism. Ms. Reiss’s commentaries in every issue are essential to understanding what is happening in the world. Her ability to place the meaning of current events in ethical and historical context, to make sense of matters impacting our lives, and to do so with honesty and style, makes her respected by readers around the world.

There is the Terrain Gallery, which has stood for integrity in the art world since its doors opened in 1955. In its exhibitions and talks, all based on Aesthetic Realism, the Terrain has shown that the technique of art is a guide to understanding our deepest and most everyday questions.

And there is the thrilling study that takes place in Aesthetic Realism consultations, where a person can learn to see his or her own self as a subject of education having to do with the world in all its width.

The principles of Aesthetic Realism make for new, urgently needed understanding and kindness between people. I know that firsthand. And I’ll say something about what has happened to me through this education—because my experience represents the great good that can come to everyone, and to America itself.

I’m grateful to say that some of what I’ll tell of here I wrote of too in my book Photography, Life, and the Opposites. At the time I first met Aesthetic Realism, I saw that it explained the beauty of photography, the art I loved, as nothing else did. But I soon came to see that it explained much more—including myself!

Something Everyone Longs to Understand

When I began to study Aesthetic Realism in consultations, I began to learn why I felt unsure of myself and so often ill at ease speaking with people. The cause was my desire to have contempt; and it took forms that it takes in millions of men and women right now. For example, I didn’t listen very well when others spoke. Often, the only parts of conversations I could remember were the things I had said. Here are just three of the questions I heard in consultations, which enabled me to change and feel proud of my purpose when I spoke with someone:

- Do you think the feelings of others are as real as your own?

- Do you put limits on how much you want to know people?

- Do you think their thoughts and feelings can add to you, make you more of an individual?

People want to feel they can be proud and humble, assertive and yielding, at the same time. They want to feel their lives make sense. The right questions can make this possible. People get to hear them in Aesthetic Realism consultations.

My contempt took other forms too. I frequently said things under the guise of “honesty” that were cruel. In my consultations I began to learn that contempt was not the valuable asset I thought it was, that my hope to find flaws in people and put them in their place actually made me less intelligent and stopped me from liking myself.

Some years later, when I began to study with Eli Siegel, he provided me with a basis for understanding a form of contempt that had been very much in me. I told him about a recurrent dream I’d had, which was also a sensation I’d have in a semi-wakeful state: I would be lying in bed and a coldness would creep over me. It would become harder and harder to breathe, and I’d desperately try to move, get free—but could not. Mr. Siegel asked, “Is there a certain triumph in not being able to feel anything—‘I know it’s you, Winifred, but I feel nothing’?” I answered, “Yes!” “Do you think,” he continued, “that not feeling can be the next best thing to ecstasy? It is a solace for the injustice we think the world does to us. I would say that wasn’t a dream, Mr. Bernstein—that was a lifestyle.”

I had preferred to see the world, including people, as having hurt me, rather than admit I’d had ill will for people in any way. Through what Mr. Siegel was teaching me, I could now criticize that fake triumph with clarity and didn’t have to punish myself for it so frighteningly. Eli Siegel’s understanding of humanity, of me, was powerful and subtle, a magnificent oneness of exactitude and compassion. And I thank him with all my heart.

What Love Is—& What Interferes

At the time my wife, Harriet, and I began to study Aesthetic Realism in consultations, we had been married for just ten months. When we’d met, I saw in Harriet a relation of intellect and body, calm and exuberance, that I found irresistible, and I also felt she had a gentleness I lacked. Yet ten months after marrying, we both felt angry and very confused.

Then in consultations I began to learn that the purpose of love is not to have a refuge from the world: the purpose of love and marriage is to like the world through a dear representative of it. Furthermore, since the person we’re close to comes from the world and has the structure of the world—its opposites—in her, we won’t see her any better than the way we see the world itself. For example, as a young man I studied the martial arts and felt I was good at spotting potential trouble. However (and this is a criticism not of the martial arts but of me), I felt driven to see nearly every person I passed on the street as a potential enemy; in my mind I annulled any possible meaning or value they might have other than as a foil for my self-aggrandizement. As a result, instead of feeling safer, I became even more afraid of the world, and also disliked myself. Then: here I was, married to a woman I was so affected by; but since I didn’t understand the contemptuous way of seeing I just described, it continued with Harriet. I didn’t know there was a hope in me to see her as an enemy too; as someone to be disappointed in, protect myself from, and triumph over.

Also, I came to our marriage with the disinclination to listen to people that I mentioned earlier. It was pretty clear to my consultants that I liked to talk more than listen, and they asked me, “If as a photographer you give your attention to something else, what does it take your attention away from for a while?” I answered, “From myself.”

Consultants. Would you say you have that question with your wife—that is, if you give your thought to her for fifteen minutes, those are fifteen minutes you can’t give to yourself?

Len Bernstein. Yes, that makes sense.

Consultants. Now, do you think it’s possible—and this is where aesthetics comes in—to feel that as you are giving your thought to something else, you are taking care of yourself?

I hadn’t thought this was possible. Often, my idea of giving my thought to Harriet was to patronizingly instruct her through little speeches meant for her improvement, and I remember how disgusted with myself this later made me feel. I saw the romance in our marriage changing into boredom and felt powerless to stop it. But in consultations I learned that boredom is really ego in disguise, the feeling that the world, including the world as represented by the person we are close to, isn’t good enough to affect us.

Aesthetic Realism understood the best and worst in me: my desire to care for the world, for art, for another person, and the contempt that interfered with it. My consultants were teaching me that the one way to take care of myself, to truly like myself, was to try to be fair to what is not myself—and I began to change.

In the days and weeks that followed, people and things took on new meaning for me. I was more excited than ever about photography, and I was prouder and happier as I became more interested in how Harriet saw—not just me, but the whole world. I came to see that the desire to know is central to love and to our integrity. And this desire to know is—I’m very glad to tell you—the height of true romance.

I am still smitten by Harriet’s looks and thoughtfulness, which first captivated me. Then, as we began to have consultations, I saw her love for Aesthetic Realism, which showed her largeness of mind and care for truth. That is what made me trust her, and why my love for her has grown with each year of our marriage.

At this point I’ll say something more about Mr. Siegel himself. I am one of many people who consider him the greatest philosopher who ever lived, and I’ve heard of no one kinder. Because his desire to know was so vast, the thousands of lectures he gave were about an encyclopedic diversity of subjects. And he brought to every subject an unparalleled comprehension. As I studied with him, I saw, too, that Mr. Siegel was completely without prejudice.

I am moved to quote here my fellow photographer and dear friend, the late Allan Michael. He wrote, “It is hard to be Black in this country and feel that justice is going to come your way,” and then he continued:

I know that Aesthetic Realism is the means to end racism. In fact, the Aesthetic Realism education is living proof that through what Mr. Siegel explained, people of one background not only can be fair to others, but can understand them. It was through the thought of Eli Siegel, a white man, that I was able to understand the deepest things in myself; and this points to a fundamental hope for all races.

Urgent—for America & Each of Us

There is nothing America and the world need more now than for people to see other people justly: to see each other with authentic respect; to see that persons one felt to be so different from oneself are also like oneself. Aesthetic Realism is the education that makes this possible. As an example, I’ll describe briefly a tremendous change in my life: how I changed about my father, Milton Bernstein.

Like many sons, when I was past a certain age, I didn’t get along well with my father. In fact, I was furious with him and, I’m ashamed to say, I got a cruel triumph being scornful of him—including through often not responding when he spoke to me. I didn’t think I had much in common with him, or that his life was interesting—in spite of the fact that he had, among other things, boxed professionally, read and loved Shakespeare, and fought against fascism in Spain as a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. When I began to photograph, I became somewhat more thoughtful about people, but I regret that I still wanted to sum up Milton Bernstein and continued to be cold to him.

Then, in my Aesthetic Realism consultations, I learned that my father and mother did not exist to make me important or unhappy: they were full human beings with lives of their own they were hoping to like. They were in relation, not just to me, but to the whole world. I was given assignments, as a means of seeing them more justly. For example: to write a character sketch of my mother at age 26; and to read Turgenev’s novel Fathers and Sons, as the beginning of a study in how the literature of the world describes the relation between parent and child. And I became kinder.

I remember the first time as an adult that I spent a whole day with my father without arguing. That was amazing in itself, but we also had a good time! It was after I had been studying Aesthetic Realism for a few months. My father had noticed a change in me from our phone conversations, and he came from Florida to visit with Harriet and me in New York. At the end of that day he said to me that at last he felt like he had his son back, and he told me how grateful he was to Aesthetic Realism for making this possible.

I’ll quote now from one of my consultations, in which my father was a guest. My consultants explained that it was important “to see where father and son have the same questions.” And they asked my father, “What would you say was your biggest mistake?”

Milton Bernstein. I refused to listen. If nobody agreed with

me—they were all wrong.Consultants. Do you think that your son has any qualities like that?

Milton Bernstein. Yes, he wouldn’t listen.

In this consultation, as my father listened to questions and spoke thoughtfully about himself, I felt a care and respect for him that was new. We both felt that we were getting a fresh start, learning how we were the same and different, and that this was in behalf of seeing all people with greater fairness. And my father began to study Aesthetic Realism for himself. I’ll never forget how he looked after his first Aesthetic Realism consultation—like a man who had seen the sun rise for the first time.

In relation to my father, I’ll give one more example of the depth of kindness and true civilization that Aesthetic Realism can make for between people. It took place some years later, at the time my father was ill with Lou Gehrig’s disease. He knew he was dying, and I didn’t know how to be with him. I was studying in classes for Aesthetic Realism consultants and associates, taught by Ellen Reiss; and, seeing my distress, Ms. Reiss asked me questions in a class that strengthened me enormously. One was: “Does your father feel you want to know all his feelings, or are you afraid to?” And she explained, “It would be good if he could feel there was at least one person who wasn’t afraid to hear all his thoughts.” I told my dad what I was learning and we got a chance to say things to each other in the final months of his life that, without Ms. Reiss’s good will, would never have been expressed.

What a Photograph Tells Us

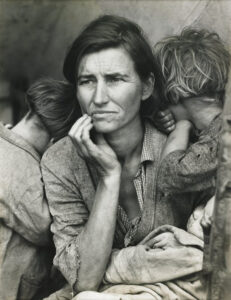

I’ll comment, a little, here on something shown only by Aesthetic Realism: that art, through the opposites, is a guide to how every person—and nation—needs to see. For example, there is Dorothea Lange’s beautiful photograph Migrant Mother, taken in 1936, in the midst of the Depression. It is a oneness of the opposites personal and impersonal, self and world, body and thought, weakness and strength.

We see the anguish of the mother: she and her children are hungry and homeless—as, shamefully, so many Americans are today. The photographer has us see this woman as personal, as real. And we need to see that people who aren’t ourselves are as real as we are.

For all her pain, the woman’s look is thoughtful, deep. Her fingers touch her face, near her lips: the gesture is expressive of so much worry; at the same time, the fingers glow with light, and they are both graceful and strong. We feel not just body but thought in that expressive hand. And it is part of an abstract, impersonal shape, a triangle, made up of the diagonals of the woman’s bent arm and shoulder. There is light on her face too, and we see in that deep face strong horizontals and diagonals. Through universal shapes and lines, we see this woman as not only personal but impersonal too: she has the world in her.

This photograph, in its technique, is completely opposed to contempt—including the contempt of seeing human beings in terms of profit, which has caused people to be poor. Dorothea Lange took several photographs of the same mother and children, but only this one shows the two children from the back. That makes them, while so personal as they lean on their mother for comfort, impersonal as well: they are not only her children—they stand for all children.

The Aesthetic Realism Foundation presents the aesthetic way of seeing people and the world, which will make for an America just to all its citizens, where people are proud of how they see each other and can truly like themselves.

Sincerely,

Len Bernstein

Aesthetic Realism Associate