The Surreal Is Everyday: The Art of René Magritte

Men and women all over the world, including artists, will love Eli Siegel, as I do, for the absolutely new and crucial distinction he made between two kinds of imagination: one that is for the world and art, and the other that is against both—and against mind itself. In Self and World, Mr. Siegel wrote:

At the present time…wonder and matter-of-fact live on two sides of the railroad. A person behaves with groomed propriety outwardly; but in his bed, or in reverie, or in just thinking to himself, there is another world. And these two worlds are seen as neighbors who need never meet. Imagination and aesthetics make for the meeting of wonder and matter-of-fact and therefore if we do not respect imagination and aesthetics consciously, we are permitting the seeds of personality disjunction to operate.

This great passage is the means for understanding what was central in the life and work of René Magritte, the Belgian surrealist. In his paintings, Magritte, who lived from 1890 to 1967, had one of the deepest and liveliest imaginations in modern art, in which “wonder and matter-of-fact” met in some of the most surprisingly beautiful ways.

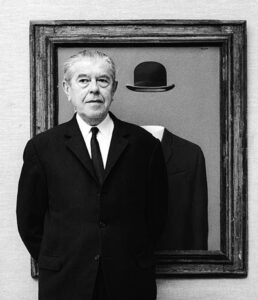

Duane Michals’ photograph of the artist shows how, for all his avant-garde views and radical politics, Magritte always looked and dressed like a petit-bourgeois. He didn’t want to stand out, but wanted people to think he was an ordinary middle class gentleman.

Surprisingly, he didn’t paint in a studio apart from his living quarters, but painted in the apartment he and his wife lived in. It was a way he had of trying to make a one of the matter-of-fact and the wonderful.

Yet, in everyday life, he could also give in to a contemptuous way of mind that separated the two, seeing people and objects as dull and “old hat.” Louis Soutenaire, a life-long friend, described him as being “at once very sensitive and indifferent.” I’m grateful to Aesthetic Realism for enabling me to see that his purpose as artist was very different; it was to use his imagination to have us see the true wonder of things—and to fight the deathly indifference of contempt.

For example, in Patrick Waldberg’s 1965 book on the artist, Magritte is quoted as saying:

In my paintings, I showed objects situated in places where they are never actually encountered. In view of my determination to make the most familiar object cry aloud, these had to be disposed in a new order to be charged with a vibrant significance.

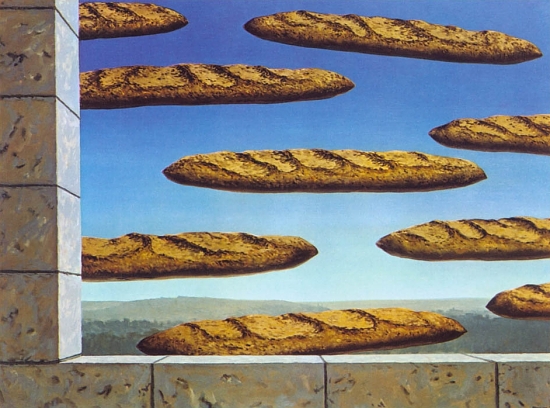

This is Legende Dorée, or The Golden Legend. Here, loaves of bread insist on being looked at anew as they float by a window. Bread on the table we can take for granted but bread floating by a window? Voilà! a Happening! To see things as happenings opposes dullness, and we have a new respect for bread.

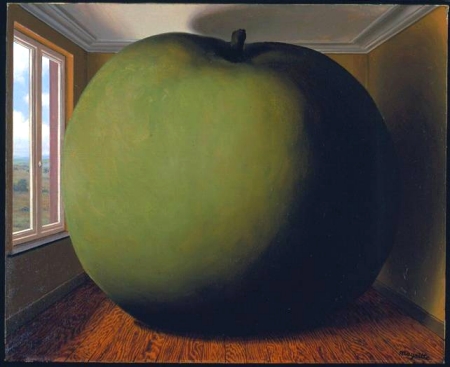

This is The Listening Room. An apple warns, “Don’t dismiss me!” Like much of Magritte’s work, this painting is both a criticism and an encouragement. The looming shape and green color challenge our desire to be contemptuous of what is smaller than ourselves. Magritte makes this object “cry aloud” against our possible contempt for it. An object is having its just revenge. A little apple you can manage easily, bite into without a second thought, patronize a bit. An apple this big, says the painter, you had better respect.

I learned from Aesthetic Realism that if you make things smaller in your mind at one time, they can seem to swell and frighten you at another. Persons have imagined, as I once did, that as I was in a room, objects swelled in size, in a way that was disturbing. I tried to counter this by drawing the forms I saw, but it was not until my contempt was criticized and respect encouraged in Aesthetic Realism lessons with Eli Siegel, that these visions themselves stopped. Mr. Siegel explained to me: “Objects will object when you have contempt for them; objects want to be seen exactly, wholly.”

In Aesthetic Realism consultations, I’ve been proud and grateful to teach men, including artists, how to recognize the difference between the two kinds of imagination, and to criticize contempt in themselves, where it begins.

George Fredericks, a young set designer from the Midwest, told us in his first consultation, “I feel insecure in dealing with people and the world around me; I’m a loner.” Mr. Fredericks told us he felt his mother and father had not been interested in one another or in him. He had summed them up and scornfully dismissed them, saying, “My mother spent all her time in the kitchen, and my father watched TV.” He also had made fun of his aunts when they visited. He had used his imagination to have contempt. Aesthetic Realism shows that every person has an ethical unconscious which says: if you’re not fair to the outside world, you cannot be sure of yourself. We asked Mr. Fredericks: “Do you enjoy finding flaws in people? Do you have a raking eye?”

George Fredericks. Oh, yes, I do. My friends have mentioned that I can be too sarcastic with people. As a matter of fact, if I don’t find people interesting or attractive, I don’t even want to talk to them. I feel I’m wasting my time.

Consultants. Do you think if a person builds himself up having contempt, seeing people as dull and old hat, he will get to feel more solid or more uncertain?

George Fredericks. More uncertain.

We wanted Mr. Fredericks to see that he could use his imagination every day, as he looked at and talked to people, the same way he used his imagination in designing a theatrical set—to bring out and increase meaning, rather than to lessen it. “When are you more proud of yourself,” we asked, “when you use your imagination to make fun of people in your mind, or when you work to have a set design beautiful?”

George Fredericks. Definitely when we’re planning a set. I do a lot of research and then we all work together and produce something beautiful.

Consultants. But in social life, do you get a pleasure saying something sarcastic that you feel will demolish a person?

George Fredericks. Oh, yes.

Mr. Fredericks was learning the enormous difference between the imagination of an artist, and the un-artistic imagination that arises from contempt. He was learning to be a critic of his own contempt, and seeing what it would mean to have the pleasure of the art purpose in his everyday life.

II. Contempt Is a Bad Relation of Opposites: We Dismiss and We Grab

Magritte as artist was critical of the desire in people to capture a thing, own it, and then get rid of it, thus making reality smaller and more “manageable.”

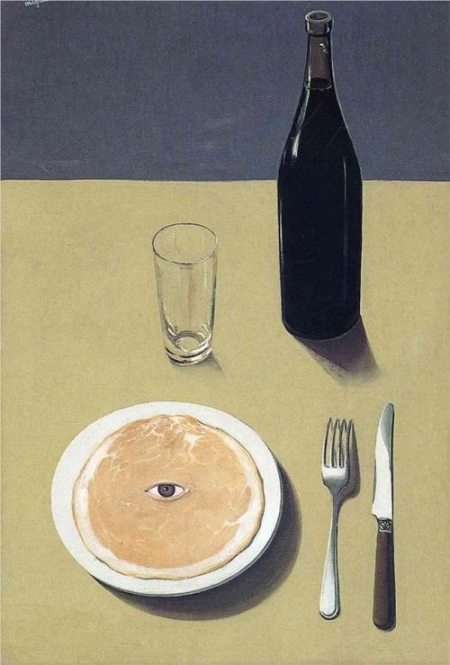

This painting, titled Portrait, is in the Museum of Modern Art. And I believe these sentences by Eli Siegel from Self and World explain what the artist must have seen and been impelled by:

Every physiological procedure, to the unconscious, is a source of power; and so is digestion. We feel when we eat that we are using the world our way….Chewing, swallowing…have their unconscious self-exaltation aspect.

The objects here all seem ordinary enough: a bottle of wine, a glass, fork and knife and plate waiting quietly, in a sense powerlessly to be used and eaten with. But from the center of the ham steak on the plate, an eye looks questioningly at us as we look at it and contemplate devouring it. You cannot escape from that eye. It sees all; I believe it is a symbol of conscience, Magritte’s conscience and ours. The eye is the world in us asking: what is your purpose with me?

In the art of Magritte, wit and sharpness are used to honor the world and the meaning of objects. But it seems that too often in his life, he used his ability to be witty in order to make fun, to mock. Patrick Waldberg relates what his brother told about the artist as a boy—that he “indulged” in mimicry. And I think that all his life Magritte shuttled between kindness and scorn, and it made him sad.

“The Surreal Is Everyday: The Art of Rene Magritte,” Continued, Part 2 … Click here