Aesthetic Realism and Expression, Part 2

By Eli Siegel

Lear and False Expression

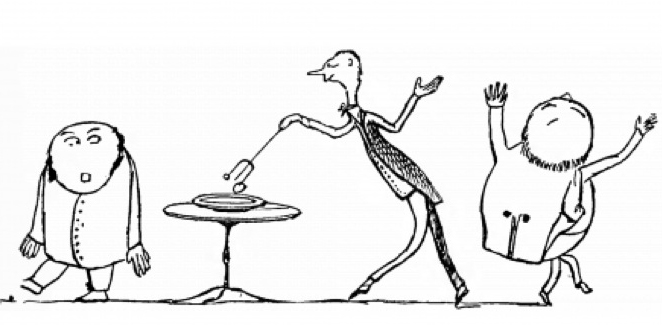

Note. The limericks of Edward Lear, Mr. Siegel has been showing, are about the various problems of expression. This is another limerick of Lear:

There was an old person of Down,

Whose face was adorned with a frown;

When he opened the door, for one minute or more,

He alarmed all the people of Down.

I have known persons who think they are expressing themselves by frowning. If they are not frowning they think they are not smart. If the word expression is to be used in its largest sense—the showing of what a thing is by what it does—a frown is a phase of expression. Since we want to impress people with how much we are going through and how much we don’t like things, we frown. Where a frown is a sign of not liking something that is ugly, it can be useful—but not the frown that people cultivate. Lear is justly showing he doesn’t like that kind of frown. Now we have one of the persons who just want to be stuck somewhere and safe:

There was an old person of Woking,

Whose mind was perverse and provoking;

He sate on a rail, with his head in a pail,

That illusive old person of Woking.

There are quite a few people like that in Lear’s poems. They get big beards in which birds can hide; they get lost somewhere; they keep on doing one thing, eating one thing. They want to solve the problem of the world by expressing themselves in only one way. For example:

There was an old person of Dean,

Who dined on one pea, and one bean;

For he said, “More than that, would make me too fat,”

That cautious old person of Dean.

People can express themselves by becoming very timid and cautious, and saying, This only is good and nothing else is.

There was an old man of Spithead,

Who opened the window, and said,”

Fil-jomble, fil-jomble, fil-rumble-come-tumble!”

That doubtful old man of Spithead.

—This represents the person who wants to express himself by being very obscure and saying things which don’t have much meaning. If you say things that no one can understand, you think you express yourself. This person does it in a fairly nice way. But the desire never to be clear is also a spurious form of expression. And persons can, of course, express themselves by deciding every week or two to become furiously angry: the anger of the week. It is spurious. No person in this world has to be angry for a fake reason; there are enough good reasons to be angry. But the fake one gives more glory:

There was an old person of Newry,

Whose manners were tinctured with fury;

He tore all the rugs, and broke all the jugs,

Within twenty miles’ distance of Newry.

Then, we have the people who express themselves by hiding:

There was an old man, who when little

Fell casually into a kettle;

But growing too stout, he could never get out,

So he passed all his life in that kettle.

That is quite sad because it pictures what happens in many lives. Children get scared, so they put themselves within limits; they get stuck somewhere. Then, when there is not much reason to be scared, they keep on being scared, and what was once seen as safety is now changed into necessity. Though there is no longer any need for the kettle, the kettle is still the limiting thing. This could be called Too, Too Common Tragedy. The same thing happens to “an old person of Bar, / Who passed all her life in a jar.” And one can see, through all these persons who get stuck, in kettles and in closets, in dishes and in pools, and in scuttles, that Lear observed something. The poems which I just read are important. They belong to the literature of the English-speaking world. Children can enjoy them—but let them; their meaning will never wear out.

Expression Is Self and World

One way of not expressing oneself is to be timid. I will read something about timidity, from a book of 1860, The Art of Conversation. Timidity means a distrust of the world around you. In all forms, that is what it is. Some timidity is obvious; but there is a much deeper timidity: many people who think they are not timid, are:

Many young men… [think being silent] gives them an air of dignified reserve. There could be no greater mistake….You are guilty of great rudeness in compelling [another person] to bear the entire burden of conversation.

Many persons want to express themselves but unconsciously think that if people try to interest them, that’s when they are important; while if they try to interest anybody else, they’re really becoming working people, and why should they? They are supposed to be amused, and also to look down somewhat on people who talk to them. “There are occasional instances of young persons…who are afflicted with reserve and bashfulness to such a degree that it actually becomes a species of mental disease. Parents say of this that ‘it will wear off,’ … but its evil effects are too generally felt, even to the end of life.” A child very early can decide that there should be a disproportion between what happens to him and what he does to others. The parents often feel—and they are abetted somewhat by professional persons in the field—this will wear out. It won’t wear out. If you have an ethical decision that makes for your glory, which you came to at the age of four, the only time it will wear out is if you find out that it is not what you want. And there is no assurance that you will find that out. You may find out that it is uncomfortable to put it into effect, and so people seem to change—but that is not a real change. The only real change is when a person says, I’m happy to change; I’m proud to change; and even if there were no trouble, I’d like to change. So people will be timid, because they think that what happens to them is not as good as what they do or what they feel. As soon as they make such a division, they cannot express themselves, because they cannot care for what they express themselves to.

Hazlitt and Expression

I go now to a writer I care for a very great deal, who had his difficulties of expression, but at the same time was one of the most likable, expressed persons who ever lived. He said when he was dying, I’ve had a happy life. He’s one of the few persons who ever talked that way: William Hazlitt, 1778-1830. In March 1788, when he was ten years old, he wrote a letter that I regard as remarkable in relation to expression. This is William Hazlitt the essayist, the critic, the rough man in many ways, but a man who wanted to enjoy so many things and also wanted to know about them. He is writing from Wem to his brother John, a painter in London:

Dear Brother,

I received your letter this morning. We were all glad to hear that you were well, and that you have so much business to do….I want you to tell me whether you go to the Academy or not and what pictures you intend for the exhibition….You want to know what I do. I am a busybody, and do many silly things; I drew eyes and noses till about a fortnight ago….Next Monday I shall begin to read Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Eutropius. I shall like to know all the Latin and Greek I can. I want to learn how to measure the stars….I begun to cypher a fortnight after Christmas….I can jump four yards at a running jump and two at a standing jump….I wish I could see all those paintings that you see….I don’t want your old clothes. I shall go to dancing this month….

I am your affectionate brother, William Hazlitt.

We’ll look at this as raising the problem of expression. “Dear Brother.” That word dear is important for expression. Can we express ourselves to people who are not dear to us somehow? Can we express ourselves without feeling that what we express ourselves to can have a foundation meaning for us? We cannot. “I received your letter this morning.” The question of expression has to do with how much we take in and how we take it in. If we cannot respond to what comes to us, we can never express ourselves. Whenever we do anything in the way of showing ourselves, there is the deepest self which is ourselves, there is what we use, and some notion of what we are showing ourselves to. All these three things have to work in a true fashion before expression can be good.

Expression Should Be Gladness

“We were all glad to hear that you were well.” When we express ourselves there should be the feeling that we are glad to do it. Even if we say that things are not going well or that we don’t like something, we have to appear proud before the expression is authentic. Otherwise it is only a whimper or a complaint or a boast. Most people, when they show themselves in any way, are not glad to. They do it reluctantly and think it is a duty. Once expression is a duty or a conquest, it is spurious.

“We cannot be happy without being employed.” All work is expression. Anything that we do can express us. If we decide to wiggle our big toe, we are expressing ourselves. If we decide that we want to take things out of closets, we are expressing ourselves—because we are doing something and our self is there. If it isn’t there, then there is something wrong. Many persons give themselves to outer things because then they can howl unconsciously and be in themselves. They suffer in order to be with themselves.

The Thought That Is Expression

Expression begins with our thoughts to ourselves. That is where we decide on who we are. And if we cannot find expression in thought itself, we won’t find expression in anything else. If a person cannot sit down, for twenty minutes if need be, and say, What I thought about added to myself, and I’m proud of the way I thought, and through thinking I came to be more myself—that person won’t express himself truly.

We have to see ourselves as we would any other thing—a lawn, a city, another person—and say, I’m thinking about what I see, and the reason I’m thinking about it is that I want to know it more; because if I know more about anything, including myself, I’m better off: We have to express ourselves through thought—not “meditation” or “revery”—but thought. We should go at ourselves in the same way as we go at the American Civil War or the Latin language or French: to know ourselves better. All thought, no matter how lonely, should be for knowledge.

“Expression” may often unconsciously take the form of saying, Now that you’re with yourself you’d better get further away from where you were; you’d better isolate yourself now and think in such a way that all that happens is that you’re roving around in the clouds that make up yourself; and in this way you’ll get away from all the knocks and sharpnesses and thorns that you had to meet.

This would be a kind of bad waking sleep, which a good deal of brooding is. Whenever a child starts brooding in that way, the question to ask is: Are you thinking, Margie, in order to know things, or are you thinking because you’re just thinking? If she says, I’m thinking because I’m just thinking, and I don’t know anything because I’m thinking—then there is something wrong with it.

When Expression Is Good

“I am a busybody, and do many silly things; I drew eyes and noses till about a fortnight ago.” Anything that a child does, or anybody does, is going to have an effect on himself. If it has a good effect it is good expression; if it has a bad effect, it is bad expression. So if a child tries to draw eyes and noses as Billy Hazlitt does at the age of ten, he’s doing it because something in him thinks he’s going to get something out of it. When expression is good, it is useful to yourself and everybody else; and if it is not useful to everybody else, you can be sure it is not useful to you either.

“Next Monday I shall begin to read Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Eutropius.” So William Hazlitt is going to be impressed by these people, and also he is going to be expressed. “I shall like to know all the Latin and Greek I can.” This has the real ring to it. What happens to you when you know something? Are you expressed more? Of course, because you have more reason to respond, and all expression is a response.

“I want to learn how to measure the stars.” He wants the sense of looking at a book, and also at the stars. What for? He wants to feel more and show more.

“I shall go through the whole cyphering book this summer and then I am to learn Euclid.” He is eager. He wants to know arithmetic and then he wants to know geometry—it’s got something to do with him.

Hazlitt said he was one of the persons most romantic about the past, and he didn’t say it just because he yearned for the past in a bad way. He felt that there were certain feelings he had had in the past which were grand. Perhaps he couldn’t keep up with them.

[At school] we…read the Speaker. Then we all set about our lessons, and those who are first ready say first. At eleven we write and cypher. In the afternoon we stand for places at spelling, and I am almost always first.

The way this is written—the sentences are short and there is a great deal to do—has liveliness. There seems to be something quite beautiful in it all. Billy Hazlitt is glad he was born. That is a good way to begin expression: to be glad you have a chance to.

“I can say no more about the boys here: some are so sulky they won’t play.” He saw that one reason people don’t want to take part in things is that they are sulky. “Others are quarrelsome because they cannot learn.” Not being able to take things in and show it, they also get quarrelsome, because if your mind is not in relation to things about you, you get a sourness in you.

In order to be entirely what we are, we have to show and do that which is in keeping with ourselves and everything else. Consequently, in order to understand the problem of expression, we have to see what we want in the deepest sense, and the aesthetics of this. There is no limit to how much the expression of ourselves is an aesthetic necessity.

♦ ♦ ♦