Vincent Van Gogh’s “Bedroom at Arles,” or, The Outside World Is Friendly

My whole life changed when I began to study Aesthetic Realism with Eli Siegel in 1942 and I learned that art was not to the side of life, but at the center of it. We can learn from the great art of the world what we are alive for: to like the world. Eli Siegel has done what no other philosopher or educator has ever accomplished: He has stated and shown magnificent evidence for this: “The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites.” It is that statement which explains what we are looking for to make sense of the world, and it explains the impulsion to art in the soul of Vincent van Gogh.

Inside and Outside: Opposites in a Friendly World

Inside and Outside: Opposites in a Friendly World

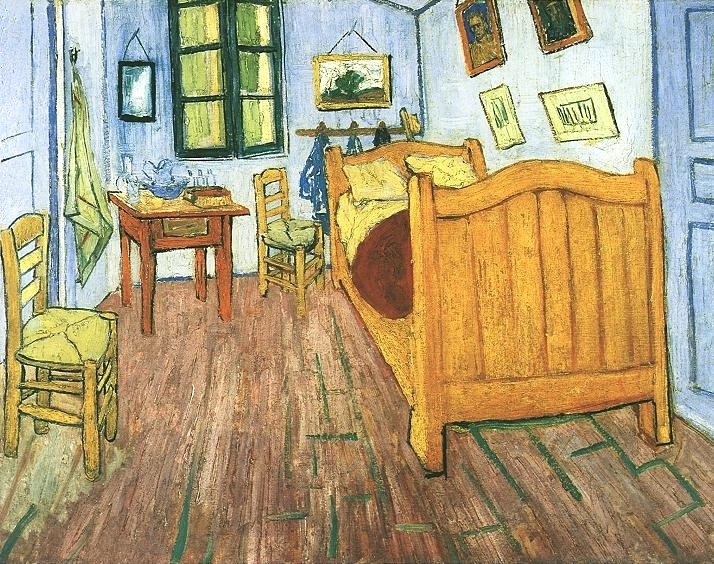

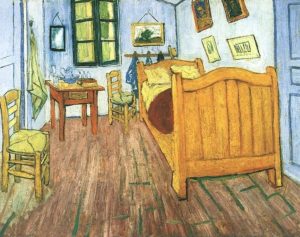

There is no front wall to the artist’s room, and the floor with its thick brown color and grassy hints between the boards combines earth and home. There is no impediment as we enter and walk right through to the sky-blue wall where the windows are active–they open in and slant out at once. And there, becoming part of the room, painted in upright, energetic strokes are the yellow and green colors of a sunny meadow, the outside landscape: the “there” is “here.”

In Aesthetic Realism lessons Eli Siegel often asked people to read Christina Rossetti’s poem “Who Shall Deliver Me?” with these stanzas:

All others are outside myself,

I lock my door and bar them out,

The turmoil, tedium, gad-about.

I lock my door upon myself,

And bar them out; but who shall wall

Self from myself, most loathed of all?

When I told Mr. Siegel that was how I felt; that I didn’t like myself, he asked me: “Do you think you could have individuality, be even more yourself, because of otherness?” Eli Siegel taught me how to open the doors of myself.

On the back wall of Vincent van Gogh’s “Bedroom at Arles” person and world become one another. A painted landscape is on one side of the in-and-out window and a mirror waiting for a person to look into is on the other side. The wall is alive with the motion of inside becoming outside, outside changing places with inside. If you look at the edges of all the rectangles on that wall you can see them dancing. That is because Van Gogh made his outlines so thick and bright with color, they move and are firm simultaneously. I think we can learn now how to have the edges of ourselves meet outside space and objects from the artist’s technique.

On the back wall of Vincent van Gogh’s “Bedroom at Arles” person and world become one another. A painted landscape is on one side of the in-and-out window and a mirror waiting for a person to look into is on the other side. The wall is alive with the motion of inside becoming outside, outside changing places with inside. If you look at the edges of all the rectangles on that wall you can see them dancing. That is because Van Gogh made his outlines so thick and bright with color, they move and are firm simultaneously. I think we can learn now how to have the edges of ourselves meet outside space and objects from the artist’s technique.

The fact that this is a bedroom makes this oneness of inside and outside all the more meaningful. In Aesthetic Realism consultations we have asked this question: “When you are snug in bed, do you feel that the outside world, the ‘there’ is present?” Most people feel this is the time to shut out the world and get some real peace. But this solution is unacceptable to our whole selves.

In an Aesthetic Realism class Eli Siegel told a man who could not sleep to hold his arms out wide and say, “World, I welcome you.” Van Gogh’s Bedroom is a visual narrative about how a man wants to welcome the outside world. First of all, the bed is enormous. It occupies the whole right wall, and as we go from front to back, the perspective is so steep, one has a sense of travelling a great distance, and of time passing, perhaps the hours of sleep at night. So, through the artist’s technique a bedroom is seen as including the time and space of the world.

In an Aesthetic Realism class Eli Siegel told a man who could not sleep to hold his arms out wide and say, “World, I welcome you.” Van Gogh’s Bedroom is a visual narrative about how a man wants to welcome the outside world. First of all, the bed is enormous. It occupies the whole right wall, and as we go from front to back, the perspective is so steep, one has a sense of travelling a great distance, and of time passing, perhaps the hours of sleep at night. So, through the artist’s technique a bedroom is seen as including the time and space of the world.

One could have a deep sleep in that soft bed, protected by the formidable footboard, and warmed by the red cover. But that yellow post on the footboard seems to me to stand for the outside world, rising up from the floor, going swiftly from front to back, cutting through the red coverlet and resting there, nestling between the pillows.

Any person who has. twisted and turned and tossed in bed can learn a lesson here: Do not forget the outside world as you lie down to rest within the confines of your bed. That yellow footboard has one side attached to the door, and the post that goes to the bed also goes up and out. It directs our eyes up over the headboard to the horizontal bar where three blue coats, the color of the sky intensified, hang half-hidden behind the slanted pillows. Sleeping and waking are so close. The message is: the outside world is with you even as you sleep.

Any person who has. twisted and turned and tossed in bed can learn a lesson here: Do not forget the outside world as you lie down to rest within the confines of your bed. That yellow footboard has one side attached to the door, and the post that goes to the bed also goes up and out. It directs our eyes up over the headboard to the horizontal bar where three blue coats, the color of the sky intensified, hang half-hidden behind the slanted pillows. Sleeping and waking are so close. The message is: the outside world is with you even as you sleep.

And there is that jaunty, yellow hat. We have traveled from earthy floor to sky-blue walls, through the bright red, round cover to the upright hat, waiting to worn by the artist as he paints under the sun.

Repose and Energy at the Same Time, for the Same Purpose

Every person wants to feel he is the same person lying down as he is standing up, the same person at his job in the daylight as he was lying in bed. This beautiful painting in its shimmering and permanent oneness of opposites shows that it is possible.

Every person wants to feel he is the same person lying down as he is standing up, the same person at his job in the daylight as he was lying in bed. This beautiful painting in its shimmering and permanent oneness of opposites shows that it is possible.

In the first part of Eli Siegel’s question about Repose and Energy in his historic Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? he asks: “Is there in painting an effect which arises from the being together of repose and energy in the artist’s mind?”

The answer is Yes. In the deep space, the spreading walls, the way the objects are placed around the edges of the room, leaving the center to move around in, we can see that the artist had a desire for motion in what he described as “inviolable rest.” Like myself, and most people, Vincent van Gogh felt that in his life energy and repose were in conflict. He described in a letter to his brother Theo feeling confined and nervous when the mistrals or storms of Arles kept him in his room, and then working outside feverishly till the sun went down. The opposites the great artist put together so gloriously in his paintings he could not make sense of in himself.

Mr. Siegel’s question on Repose and Energy continues: “Can both repose and energy be seen in a painting’s line and color, plane and volume, surface and depth, detail and composition?—and is the true effect of a good painting on the spectator one that makes at once for repose and energy, calmness and intensity, serenity and stir?”

I think the effect Eli Siegel describes is what makes so many people love this work. The red cover on the bed for instance, in its soft brightness, in the way it is round on one side, and made straight on the other by the vertical yellow post, has energy and repose simultaneously. A bed, associated with repose, is bright and given motion through the assertive energy of red and its diagonal slant. The upright table is alert and at rest at once. And what is the effect of this interplay of forms and colors? — “serenity and stir” at once.

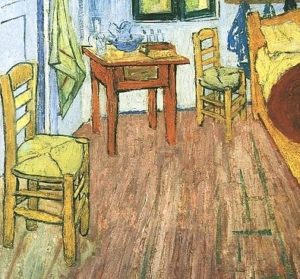

The chairs in Vincent’s painting also resolve the debate between energy and repose. They are upright, but not stiffly immobile, their position is firm, sturdy, and yet casual. They are not stuck the way I felt sometimes, and they are not “feverishly in motion.” The yellow chair which is in deep space in the center of the painting makes our eyes rest there, and yet it fairly quivers with that “yellow like fresh butter” color the artist describes in his letters, and the outline has edges that are both enclosed and open.

The chairs in Vincent’s painting also resolve the debate between energy and repose. They are upright, but not stiffly immobile, their position is firm, sturdy, and yet casual. They are not stuck the way I felt sometimes, and they are not “feverishly in motion.” The yellow chair which is in deep space in the center of the painting makes our eyes rest there, and yet it fairly quivers with that “yellow like fresh butter” color the artist describes in his letters, and the outline has edges that are both enclosed and open.

There are two chairs, so our eyes move from one to the other. The chair on the left is on a greenish patch of floor, and it seems to lead one out the hint of a doorway. The chair near the bed seems to turn to look at the red coverlet. And every piece of furniture in the room has legs, so what is seemingly at rest has implied motion. The whole painting tells us in every loving detail that the motion to and from, inside and outside can occur in a friendly world; a world in which calmness and intensity are one.

The infinite kindness of Aesthetic Realism is in seeing the deepest desire of every person: to like the world, and in showing that the only way we can do so is seeing it as it truly is — a oneness of opposites. This is the true meaning of art, it is the purpose of this beautiful painting. I am very proud to say that the Aesthetic Realism of Eli Siegel can bring the true meaning of art to the life of every person.

¹Terrain Gallery, 1955; reprinted by the Aesthetic Realism Foundation: New York

Dorothy Koppelman (1920-2017), artist and Aesthetic Realism Consultant, taught the Critical Inquiry, a workshop for artists, continued now by her colleagues Marcia Rackow, Carrie Wilson, & Ken Kimmelman. Her talk is from a series of Terrain Gallery talks given free to the public.

Copyright © 1999-2019 by Dorothy Koppelman. All rights reserved.