Aesthetic Realism and Expression

By Eli Siegel

Expression is a word much wider than at first it seems. Often it is associated with something artistic, but it doesn’t have to be. It is anything we do having an outward form, for some purpose of ourselves. In a still wider sense, it can be defined as the showing of what a thing is by what it does. Whenever we do something, we show what we are and also what we want. No person can do anything without expressing himself in some way. The question is how successful the expression is.

A writer whom I regard as important—Edward Lear—dealt a great deal with expression. His limericks are really about the problem of what a person should do about saying and doing too much, too little, or just not being interested.

How we express ourselves is how we choose to complete ourselves by what we do; because the purpose of expression is for it to come back to us and to have some effect on us, while at the same time being useful to everything else. If anyone asks himself, Would I like to think I did anything that didn’t show myself and at the same time have a good effect on myself?, the answer would be, No, I’d like to think that everything I did, even twiddling my thumbs, had some good effect on me and some meaning. We wouldn’t like to think that anything we did, did not show ourselves in a good way. We can avoid thinking about it, but the question remains. Often we do something which doesn’t seem to go along with us, and don’t do something which would go along with us.

To express ourselves, therefore, would be to do that which our selves would be most pleased with and most benefited by. That’s a hard job.

Lear, in his first Book of Nonsense, has the following:

There was an Old Man on a hill

Who seldom, if ever, stood still;

He ran up and down in his Grandmother’s gown,

Which adorned that Old Man on a hill.

A lot of people spend their time going “up and down”—going through a great deal of motion which is repetitive and useless. This is a kind of expression, because everything we do is expression. If we decide to yawn, it’s expression. If we decide not to listen, it is expression: we are saying that is the way we want to show ourselves to ourselves. The first person we express ourselves to is ourselves. If we say pooh, we are expressing ourselves to ourselves even if nobody hears us. The question is: what kind of expression are we going through? Here expression can be seen in its original meaning: the pressing out of something from ourselves.

The activity described in this limerick would be a useless action; and a good deal of expression is superfluous. You go through a lot, but if your self is not in it, it isn’t really expression; because expression is something that, if it’s complete, takes in depth and surface. We can play tricks with depth and surface. Like the person described here, people can dress to express themselves: I want to wear this—I’ll express my personality that way, even though other people may look askance and even laugh a little!

Where Expression Begins

Nagging is expression; making a nuisance of oneself is an expression—because expression isn’t only good expression. Expression is anything we do which shows what we are and what we want.

Most people associate expression with activity. Yes, expression is activity, but it begins in ourselves. If we think that when we are brooding about something, thinking about something, feeling something, we are giving ourselves an outside form, then we are expressing ourselves. Expression begins with how we think.

If our thought doesn’t give ourselves an outward form, it is not expressive thought. And most thought, particularly the brooding, gloomy thought, is not expression. It is all an inside job. When a person is moping, it is not expression, because the self is not looked on as if it were acted on, or seen as an object.

In every instance of expression the self must be put outside. Expression has to do with the word express (press out). The business of the self doing a murky job in itself is not expression. In fact, it’s poison. People don’t know that they are doing it, but every time they are, they are hurting themselves. To express means that you see yourself as an outside thing, and you send yourself abroad.

There was an old person of Wick,

Who said, “Tick-a-Tick, Tick-a-Tick;

Chicabee, Chickabaw.” And he said nothing more,

That laconic old person of Wick.

One thing people do is imagine that they are expressing themselves by restraining themselves, by not talking. They think that by keeping themselves to themselves and doing as little as possible, they are expressing themselves. About that, Aesthetic Realism says very carefully, even solemnly, and most decidedly: Phooey! This limerick presents a person who is trying to limit himself and thinks in limiting himself he is expressing himself. He gets very laconic. He won’t say three words if they are necessary, if he can get by with saying a word and a half.

There was an old man at a Station,

Who made a promiscuous oration;

But they said, “Take some snuff!—You have talk’d quite enough,

You afflicting old man at a Station.”

Expression is never expression until it’s complete and also accurate. If you just say anything, and let yourself slide, that is not expression. There is no true expression except that which you are proud of. Throwing a stone at somebody or calling somebody a name which that person doesn’t deserve is not expression, because true expression is that which shows the whole self taking an outside form. If the whole self is not taking an outside form, it doesn’t join with a friendly outside. Your “expression” is only an expression of ailment and death; because anytime part of the self is expressed and the whole self is not, we are saying, Unhappiness, come to me, and ailment, join me. Anytime we indulge in an anger we’re not proud of or say things we don’t want to say, we are adding one bit more of deleterious matter to ourselves.

Three Problems of Expression

There was an old man of Hong Kong,

Who never did anything wrong;

He lay on his back, with his head in a sack,

That innocuous old man of Hong Kong.

Many persons think that they are expressing themselves by going to sleep, particularly when there is company. That is a triumph of a sort, but it is most definitely toxic. This kind of person is described by Lear in this jaunty limerick: he solved all his problems by not having any.

There was an old person of Fife,

Who was greatly disgusted with life;

They sang him a ballad, and fed him on salad;

Which cured that old person of Fife.

This limerick represents the two kinds of things that should be present with us: “They sang him a ballad, and fed him on salad.” A ballad stands for poetry, something which has to do with mind, which isn’t immediately about oneself; and salad is food. When we can put together these two foundation ways of using the world, thought and food, and see them as one in the deepest sense, we are in a position to go after useful expression.

There was an old man who screamed out

Whenever they knocked him about:

So they took off his boots, and fed him with fruits,

And continued to knock him about.

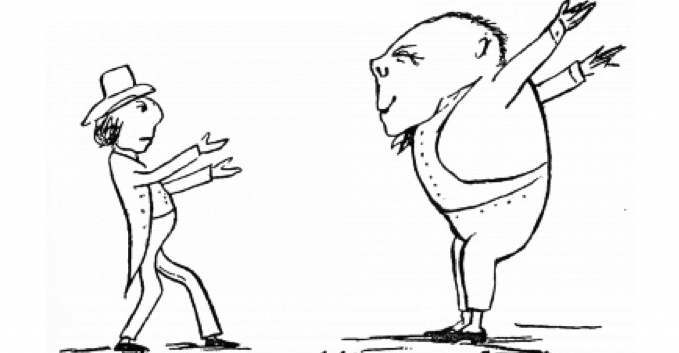

In Lear’s illustration of the limerick, this man who screamed out seems to be quite joyful, but at the same time what seems to be necessary for him is quite vigorous objective notice from others. This is important because one way of getting expression is to be shaken about. Most people are much afraid of that. But in the same way as it is necessary sometimes to stir things to do a better job of cooking, so it is necessary to have ourselves stirred because we have to be impressed before we can express ourselves. Part of the being impressed is the being stirred. If in the field of thought we have put up so many guards that we can be immune to anything deeply exciting, we’ll never express ourselves. People have to be stirred—and not just superficially.

♦