The Surreal Is Everyday: The Art of René Magritte, Part 2

III. The Art Imagination Is Both Critical and Kind

In an Aesthetic Realism class I attended in 1964, Eli Siegel showed that aesthetics, the making one of opposites, is the only answer to the shuttling that troubled Magritte as it does most men. He said to me:

In our effort to be strong, we may be unkind. Be kind with accuracy. Accuracy is the cool aspect of kindness. Say something that is sharp and has feeling at once. When we’re kind, we don’t feel sharp. When we’re sharp, we don’t feel kind. Aesthetic Realism says we can be both at the same time. It is necessary to be.

It was necessary for Magritte; all his paintings show this is what he wanted. The painting Intimate Journal, painted in 1951, is a work I care for, because I believe it shows the artist’s deep desire to melt, be kinder, and at the same time maintain himself. Here, one stone man is gently taking out a speck of dirt from another stone man’s eye. Magritte has shown that living men can turn to stone, be unfeeling; then, in an act of kindness, they become softer, yielding with accuracy, sharpness, and point.

Eli Siegel was himself kindness as accuracy, accuracy as kindness, and he taught me a new way of seeing the world, as he might have taught Magritte. The Belgian artist was looking for someone to take impediments from his eyes, too. I think he wanted to be comprehended, as I was.

In a class, Mr. Siegel talked to me about the problem of how to get together kindness and criticism. He said:

In art, pity and satire, comprehension and objection can be related and be one. In all art there is compassion. But we so want to be up in arms about the wicked, we have no time to feel, “Isn’t it regrettable things have become that way?”

IV. Imagination When Alone and with People

A question I had years ago, which I recognize in Magritte, was: how much to be alone and how much to be with people? My solution then was to have some time when I was part of the crowd, lively, social, funny and having a great time: then, at a certain point I wanted to be alone, having my own grim thoughts, using my imagination to feel unappreciated, misunderstood. At these times, the appearance of other people was an unwelcome, even hostile invasion. In an Aesthetic Realism lesson, Mr. Siegel asked me: “When you are alone, do you like your thoughts about other people? Are they kind? Are you dismissing people?” And he asked me: “When you paint, does it make you kinder to people, or less kind?” I said, “Definitely kinder.”

I wish Magritte could have learned what I did. Patrick Waldberg describes how Magritte was troubled by the difference in the way he felt alone and then with people. He writes:

In daily life he is prey to perpetual ambivalences. On one hand he hates being alone. Yet to have to get out of the house, pay a visit, see people, these are painful prospects for him; nevertheless, out he goes, there’s no holding him back. Contact with fellow men is precious to him, and also unbearable. He is eager to communicate, receptive, hospitable; but it’s not long ere one detects a shadow of disappointment creep over him, sometimes even the beginning of impatience.

Aesthetic Realism teaches that the only way to be alone and be able to trust one’s thoughts is to like the way you think about other people. It is the artist’s purpose, and it should be our purpose all the time.

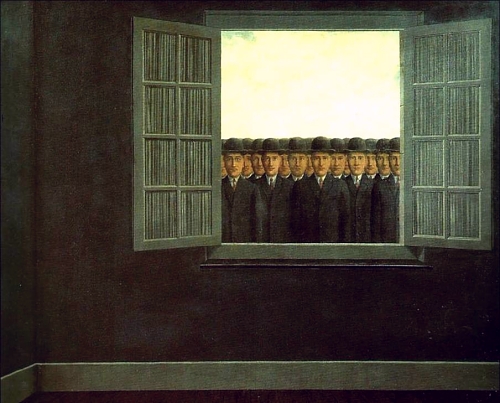

Here are two paintings in which the artist shows how much he wanted the outside world to intrude, even invade his private world. In Month of the Grape Harvest, we are inside a bare room, confronted by a crowd of almost identical looking men, peering in from the outside. They have something of the anonymous quality of a Greek chorus, they are the People; if we try to shut them out, they come to windows to confront us.

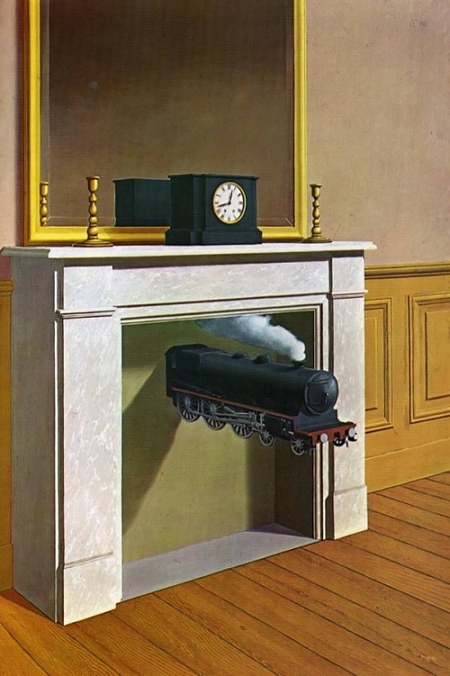

Time Transfixed is probably one of the most popular of Magritte’s paintings. It is about excitement and peace, wanting things unpredictable and noisy on one hand, quiet, predictable and neat on the other.

This scene puts together the shocking and the precise. The forms are crisp, the room tidy, the colors are quiet and bland, yet they have a strange intensity. The humdrum becomes wonderful. Just look at that small locomotive. It disturbs the fireplace, often the center of comfort in a home—and enters our consciousness much the way the eye in the ham steak did. The propriety of this room is at once composed and disquieting, frozen and in motion. The circle in the nose of the locomotive is like that of the clock above. The geometric forms of the noisy intruder from the outside world are related to the rectangles and circles of the room. This room shakes us up and composes us at once, and I’ve learned from Aesthetic Realism, that is the purpose of art itself. This is the feeling, too, I’m so grateful to have experienced in Aesthetic Realism lessons with Eli Siegel.

In Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? Mr. Siegel asks about Heaviness and Lightness:

Is there is all art, …the presence of what makes for lightness, release….Is there the presence, too, of what makes for stability, solidity, seriousness?—is the state of mind making for art both heavier and lighter than that which is customary?

Every person has the question of being serious, being meditative and also being light, feeling unburdened. Magritte was a particularly rich mingling of profundity and high jinks. In the following he is decidedly philosophic; at the same moment, he is comic as he describes his intention as artist:

The creation of new objects; the transformation of known objects, for certain objects a change of substance, a wooden sky, for instance….

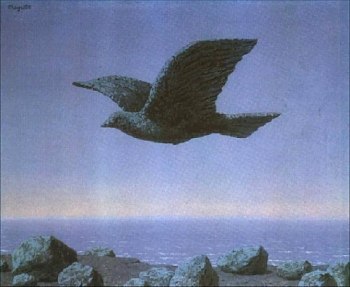

Rene Magritte had the human problem of fixity and motion, related to heaviness and lightness, and that problem is present in The Idol, where a stone bird is too immobile and heavy. We do not feel weight has become light beautifully. I believe Aesthetic Realism explains the technical difficulty in this and other paintings by the Belgian surrealist. He never decided wholly which made him free, being separate and away from people, like a bird flying alone in the sky, or being of the selves of other people and the diversity of the world. This bird is heavy and stuck. It represents a false notion of freedom which I’ve learned we don’t have to be stuck with. This is certainly one of the most important ways I have changed through my study of Aesthetic Realism.

Magritte questioned his work, and I believe rightly so. Good as he is—and I care for him a great deal—a certain divine expansiveness, infinite yet exact, too often eludes him. One senses in his work something which impedes an easy flow between object and object. There remains a feeling of something too contained, still sealed. Patrick Waldberg relates this important conversation with Magritte in 1964:

He gestured wearily toward the wall where his pictures hung, then said: “I know. There’s something wrong there, in all that something which fundamentally doesn’t work. I don’t know exactly what, but it would be worthwhile finding out—more worthwhile than just saying it’s fine as it is.”

And Waldberg comments:

Clearly, in calling for this unsparing examination of his work…he was voicing a far-reaching concern, a question relating to the whole of his life’s endeavor and the direction he had taken.

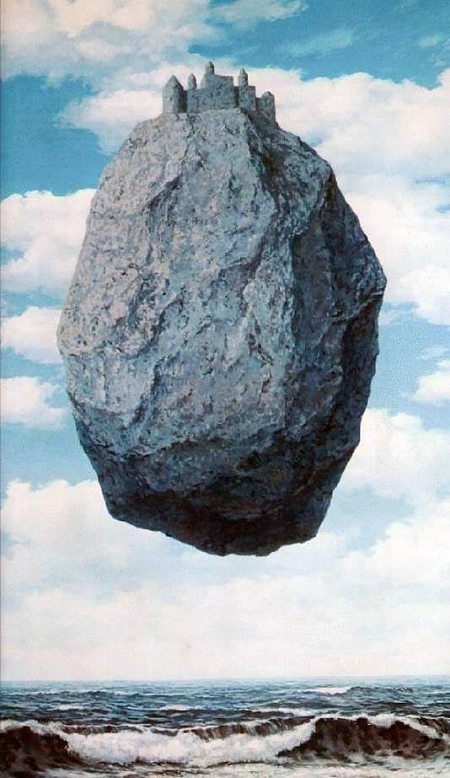

In Castle of the Pyrenees of 1959, however, heaviness and lightness work together for one purpose and the painting is beautiful. The massive and rocky has successfully and surprisingly been made buoyant and light. Magritte presents an impossible situation, an imagined situation, solidly, substantially. Painted almost photographically, we believe what is happening.

The heavy rock and castle, floating in space, become lighter and their pale bluish color shows they are also somewhat insubstantial and spacious, like the atmosphere around them. The symmetrical design makes for a feeling of sobriety in the midst of humor. We feel something like religious awe at what is happening, something large and grand, with all time and space present.

I love these sentences by Ellen Reiss from an issue of The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, which describe the thought, the imagination, that makes for beauty:

All real art, however wild, Aesthetic Realism shows, is impelled by the desire to get to truth. It is impelled by the fervent feeling, “I want to see this thing”—this subject of an artwork—“in all its fulness, its depth, its mystery, its meaning. I want to get to what it is and show it; in fact, I want to take orders from what it is, have the truth about it run me, and not have anything narrow in me get in the way. And I see this as my expression.”

Every artist and every person can have his and her life be more like a work of art, be more beautiful. We can learn how to. That is the grand and kind purpose of the Aesthetic Realism of Eli Siegel which I have the honor to study and teach.

♦ ♦ ♦

Chaim Koppelman (1920 – 2009) was one of the earliest artists to see the value, for both art and life, of the philosophy Aesthetic Realism. He began to study with its founder, the poet and critic Eli Siegel, in the 1940s, and was on the faculty of the School of Visual Arts and the Aesthetic Realism Foundation for many years. In 2011 the Museo Napoleonico in Rome, Italy had a major show of his work titled “Napoleon Entering New York: Chaim Koppelman and the Emperor.” This paper on Magritte was first presented in1998 as part of a public seminar titled “What’s the Difference between Imagination in Art & in Everyday Life?”

Back: René Magritte, Part 1 … Click here

Related Articles:

Power and Tenderness in Men and in Picasso’s Minotauromachy by Chaim Koppelman

Wonder and Matter-of-Fact Meet—The Imagination of Beatrix Potter by Marcia Rackow

Picasso’s Dora Maar Seated—or, Full Face and Profile: How Do They Show the Self? by Meryl Simon