Philip Guston: The Man, His Life, & His Work

By Dorothy Koppelman

Continued, Part 2.

It is to Guston’s credit that he was not able to smother that fight in himself between the desire to see, which is in those beautiful paintings we can look at now, and the desire to have a kind of strutting—and painful to himself—contempt.

He was a victim of the press boycott of Aesthetic Realism and of his own snobbishness. From l94l to l947 teaching at the University of Iowa Guston knew several persons who spoke to him of what they were learning from Eli Siegel. Guston’s desire to find the outside world against him and his refusal to see the beautiful evidence that contradicted that hope, made him deeply despise himself. I think that when he won a Guggenheim fellowship and a prestigious Prix de Rome, and left for Venice in l948 he may have been proud of his work, but felt he did not deserve a certain praise for his soul. In Rome, he wrote of how he “suffered a depression” and could not paint. There is a dark, angry way of seeing in his abstract drawings—dark blacks literally dig into the paper. There is a painful relation of confusion and abstract form.

He was a victim of the press boycott of Aesthetic Realism and of his own snobbishness. From l94l to l947 teaching at the University of Iowa Guston knew several persons who spoke to him of what they were learning from Eli Siegel. Guston’s desire to find the outside world against him and his refusal to see the beautiful evidence that contradicted that hope, made him deeply despise himself. I think that when he won a Guggenheim fellowship and a prestigious Prix de Rome, and left for Venice in l948 he may have been proud of his work, but felt he did not deserve a certain praise for his soul. In Rome, he wrote of how he “suffered a depression” and could not paint. There is a dark, angry way of seeing in his abstract drawings—dark blacks literally dig into the paper. There is a painful relation of confusion and abstract form.

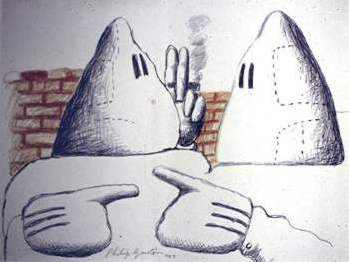

Then he did these drawings with their mingling of poignancy and self-mockery, their comic-strip feeling. These works fairly shout their self-criticism but not a single art critic saw that the artist did not like himself. About these works, Guston wrote: “I perceive myself behind the hoods.”

Then he did these drawings with their mingling of poignancy and self-mockery, their comic-strip feeling. These works fairly shout their self-criticism but not a single art critic saw that the artist did not like himself. About these works, Guston wrote: “I perceive myself behind the hoods.”

I attended a talk given by Mr. Guston at the Museum of Modern Art in the early l950s. The artist was talking about how artists have been misunderstood, and that comprehension was really impossible. During the discussion period I told Mr. Guston that in my study with Eli Siegel my hopes as a person and my intention as an artist had been greatly understood; I had heard the criticism and encouragement every artist hopes for. I was studying Eli Siegel’s great Aesthetic Realism principle: “The resolution of conflict in self is like the making one of opposites in art.” Guston hurt his heart, his mind, his life by acting as if he did not want to hear what I was saying. Like many artists, he got such a mistaken false glory out of feeling he could not be understood. The harm of this contempt for the minds of people is incalculable.

The Technique of Liking Ourselves is the Technique of Art

The hope of Philip Guston to like himself and the world at the same time is in one of his most beautiful works, “To B.W.T.”—another artist, Bradley Walker Tomlin. There is a oneness of almost congested thickness, a hint of depths, a shimmering back and forth of weight and dull darks and glowing oranges—and then a spreading resolution of two things—one, the discomfort of weight and the other a wide lightness. Luminous pinks, warm greys; and the glowing red-oranges play in a vertical and horizontal melody with soft greens, dull pinks. Solid depth is simultaneous with a pulsating light on a surface.

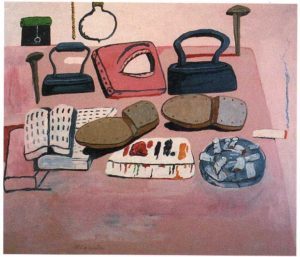

To Eli Siegel’s liberating question Is Beauty the Making One of Opposites? this painting gives a great and lasting Yes; one feels the “serenity and stir” Mr. Siegel described as the effect of all good painting. When Philip Guston changed his way of painting and showed in an exhibition in l970, he said he wanted to be close to “thingness,” to the “images of things.” I admired that desire immensely. I believe he wanted to declare his sameness to other graspable objects, to see objects as criticism of his desire to hide. “Painter’s Table” says I am like you, irons, boot soles, nails, books, round cigarette ashtrays and round light bulbs. Don’t we all share a pink table—pink like my flesh?

“Flatlands” is a lineup of hooded heads, a pink foot, fingers, clocks, a jolly pink sun, and two hooded heads confronting one another, all sharing a democratic surface—no disproportionate, self-assertion here.

The principle we have to go on, to study, in order to like ourselves is this, stated by Eli Siegel: “In reality opposites are one; art shows this”—and reality includes ourselves.

In Aesthetic Realism consultations we ask, for instance: “Are you like this table?—hard and soft, rough and smooth? Is this a warm color?—How does the color go with the hard edges of the table? What could you learn from this table?—Are you the same and different from other people who have reality’s opposites in them?

When we feel both “snug” under our skin as Eli Siegel has described it and at the same time, we like “All That,” the actual objects, the streets, the rain, the wind, having flatness and depth, force and gentleness, coldness and warmth we are experiencing the lovely oneness of self and world and you are liking yourself.

Looking at Philip Guston and his work I am grateful that their heretofore mute message, so poignantly waiting, became clearer to me through what I learned from Aesthetic Realism: the purpose of art, like the purpose of life, is honestly to like the world.

♦ ♦ ♦

Dorothy Koppelman is a painter, founding director of the Terrain Gallery, and on the Aesthetic Realism faculty. This discussion of Philip Guston was adapted from her paper “How Can We Really Like Ourselves?” given as part of a seminar at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation, l4l Greene Street, New York City, on Sept. l8, l997.

Back: Philip Guston, Part 1 … Click here