Aesthetic Realism and Hope

(1949)

By Eli Siegel

Most people don’t think that hoping is an exact thing. There is something corresponding to the manic-depressive state in every one of us: the person who changes from thinking he can do everything, to one who thinks he can’t do anything; a person who thinks he can cross the Pacific because he has a new way of flying, and then thinks that he can’t eat an egg because his stomach is made of glass. That is going pretty far; but there is a tendency to play around with the materials of the world—to fear them too much, and to think they are too much our own. The only way out of it is to think that there is a constant relation between the way things wholly and imaginatively are and what we want. If we want or hope for something and that something is based on the world other than as it is, then we think that the only way to be happy is to distort the world. If we think, on the other hand, that the world can be something to suit our hopes, because being itself can change, then our hopes are sensible.

I mean by hope, as I have said in Definitions, and Comment, pleasure now from the feeling that pleasure may be. Fear is pain now from the feeling that pain may be.

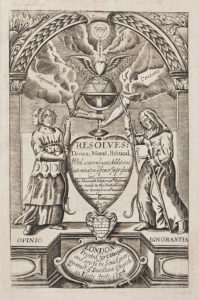

Hope can be tremendously silly, and yet it is so very necessary. This was said by a young man, Owen Feltham, whose Resolves, Divine, Moral, and Political, published in 1628, seems to have brought solace to worried persons in the seventeenth century. Feltham’s essay “Of Hope” shows how hope, though necessary, can also be so hurtful:

Hope can be tremendously silly, and yet it is so very necessary. This was said by a young man, Owen Feltham, whose Resolves, Divine, Moral, and Political, published in 1628, seems to have brought solace to worried persons in the seventeenth century. Feltham’s essay “Of Hope” shows how hope, though necessary, can also be so hurtful:

Human life hath not a surer friend, nor many times a greater enemy, than hope. It is the miserable man’s god, which, in the hardest grip of calamity, never fails to yield him beams of comfort. It is the presumptuous man’s devil, which leads him awhile in a smooth way, and then makes him break his neck on the sudden …. How many would die, did not hope sustain them! How many have died, by hoping too much! This wonder we may find in hope; that she is both a flatterer and a true friend ….

One thing is clear: Feltham hasn’t made up his mind entirely about hope. Some people suddenly think their son is dead, or a child has been run over, or somebody is never going to come back—these fears can be very sudden. And likewise, hope can be very sudden. A person gets a hunch—a wonderful thing is going to happen! There is a tremendous disposition to get to the evil of the world quickly, and also nice things quickly. These dispositions come from the same source. A person who wants to manhandle or womanhandle the world by making it altogether his own, by saying “You’ve got to be my way,” will punish himself by getting all kinds of fears. If we cannot think that there is a oneness between what goes on in our mind and the way things really are, we will have to make things worse than they are or better than they are.

We can feel that the world is better than we’ve ever known it to be. I also say that the world is worse than we have known it to be. I think this is sensible. If we can stand this fact, we shall be seeing the world truly. Otherwise we are going to go through all kinds of tricks. A mother, for example, can feel that her son is going to win a prize at school. She has no evidence for it; and then when her son comes back without the prize she feels defrauded. The same mother can think that this son is going to be run over that day. The reason she does both of these things is that she thinks the world is her husband with whom she can take liberties: she thinks the world isn’t something to be known; it is something to use to suit your mood. Once we give way to that, we get moods so deep we don’t see them, and we use the facts as an unconscious plaything. When we’re riding high we can make things so elegant that the idea of any opposition seems far away. But then we can also punish ourselves so terribly that our fears have all the boundlessness of our hopes.

There is a kind of hope that makes a woman say without any evidence, “But you said you would be with me always!” The man says, “When did I say that?” In the same way that we can hear people saying things about us that are bad because we are in a mood to punish ourselves, so we can hear all kinds of nice things that also weren’t said. Both come from the same source: we think that the world isn’t good enough to be known by us; it should be handled before it’s known.

So the kind of hope that comes from our desire to have the world do what we want, dance to our unconscious tune, can be a very bad thing. It can make us think we can play the violin when we can’t. It can punish us by making us think we can’t play the violin when we can. It is the one kind of hope we have to be afraid of. And it is why all the talk of confidence will never do any good: because what a person wants to know is where confidence changes into stubbornness.

Where our hope is based on a love of what’s true—which is the same as a love of what’s real, which is the same as a love of what the world is—that hope is healthy. If it’s based on anything else—on hunches, on tips, on feeling that tomorrow we’ve got to win at poker or pinochle—it is a very delusive thing. And even if a person won, it would mean that he was managing the world to suit himself, and he would have contempt for it.

Hope—Beautiful and Ugly

A good many people grow weak because they have hoped in the wrong way and feared in the wrong way. Feltham says hope “is the presumptuous man’s devil, which leads him awhile in the smooth way, and then makes him break his neck on the sudden.” A person can use hope as a way of showing conceit: he’s decided that it’s got to be so, and it’s got to be so. Hope can be a form of conceit, and hope can be a beautiful love for the world. Where a hope is based on a belief in the outside world, and therefore a belief in ourselves, it is good. But where it is based only on a belief in ourselves without a corresponding belief in the goodness or sense of the outside world, even if it is successful it is a corrupt and a diseased thing. The thing that we should hope for comes from the true combination of what we are and what the facts are; not from either the facts alone or ourselves alone.

Many porch climbers and burglars are actuated by hope. They hope that no policeman will be around. They hope that whereas other people haven’t gotten away with it, they will. Every person who has the nerve to do something particularly awful is a person who has hoped.

“This wonder we may find in hope; that she is both a flatterer and a true friend.” Yes. A person can encourage another, give him hope and be a friend. But he can also not be a friend. He can say, “Oh, go ahead, do that. You ‘re just as good as he is. You know just as much as he does.” The man does it, and gets into some kind of mischief. A friend very often flatters one and gives one a false sort of hope. The opposites meet insofar as honesty that encourages is also honesty that criticizes. Criticism and encouragement become one whenever we tell the truth—when our purpose is not to have a person feel he has the strength already, but to bring out the strength which he can have.

We all believe and hope that the sun will shine tomorrow, and that there will be a tomorrow. And we have the beautiful prayer “Now I lay me down to sleep. I pray the Lord my soul to keep.” We have the feeling that we are going to be, and that because we put seed in the ground things will grow. There is a certain unconscious sober hope about the cause and effect of things, which we all have.

If a person is in some kind of trouble, how much belief he has in things in general will make him able to sustain his trouble. Suppose you lose all your money; you lose the best job you ever had; suppose the wrong people get power. A person who has spent his time looking at things truly won’t go down as swiftly as the person who has never believed that things could make sense at all. Let us say that something terrible happens personally. One person, perhaps a mother, who has a faith in the world will be sad—but she won’t try to make everybody else miserable; she won’t think that the whole world has come to an end; and yet she will show her grief in a true way. Let us say that neo-fascists come into power. Some people may look upon it as a horrible thing, but never for a moment will they believe that the universe and America are permanently to be fascist. The enemy of neo-fascists is reality, consciousness of the world. They weren’t born into a world that is going to end up being neo-fascist.

A great question is, How are we going to hope? What is the basis for our hope? Do we hope in the best way? Do we fear in the best way? People are interested chiefly in the specific hope or fear of the day. Aesthetic Realism is interested in the manner of our hoping in general.

People can hope that they like nobody and that the world is disorderly, so that they can run off into themselves and complain, “You see, I was born into a world that is so dull, I’m just wonderful.” A person should ask, “Do I like the way I hope?” If we don’t like the way we hope, we’re accepting a big setback.

Feltham has the sentence “He that hopes for nothing will never attain anything.” Some people, in order never to be defeated, hope for nothing. You might as well imitate Death Valley—it never hopes for anything, apparently.

The one big hope we should have is this: since the hours, minutes, days, and weeks exist so that we have a chance to be all that we can be—not better than other people, not impressing other people—we should hope that we really be fair to those minutes, hours, days, and weeks, and fair to the material through which we can come to be all that we can be.

There are many women on in years who say, “What have I got to hope for in this world?” Any time anybody, at any age, puts all her hopes in the next world, you can be sure that reality or God doesn’t like it. This world wasn’t made so you can skip it. But people evade the possibilities of this world by having a world in themselves which is more important, which gets tied up with a certain world beyond this one. The world that is wonderful is next door to the world that is under our fingertips, a world we have to see as a representation of the wonderful world.