Jane Jacobs—and the Fight in Every Person

between Managing & Knowing

By Barbara Buehler

A talk presented in Athens, Greece, at the Annual Conference on Architecture in 2013.

I’m very happy to be speaking here today about aspects of the life and work of the American urbanologist Jane Jacobs. My critical basis is Aesthetic Realism, the philosophy founded by the great American poet and critic Eli Siegel. Its principles, as I will show, comment centrally on her work as well as the virulent opposition it often met.

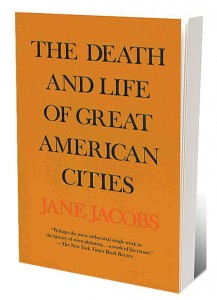

In 1961, Ms. Jacobs wrote a book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which—though its author had no academic “credentials” in urban studies—transformed the profession of urban planning in the United States, as well as the way US cities themselves were seen. I believe the reason Ms. Jacobs had such a big, good effect is explained in essence in these sentences by Eli Siegel from his Definition of “kindness,” published in the international journal The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known:

In 1961, Ms. Jacobs wrote a book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which—though its author had no academic “credentials” in urban studies—transformed the profession of urban planning in the United States, as well as the way US cities themselves were seen. I believe the reason Ms. Jacobs had such a big, good effect is explained in essence in these sentences by Eli Siegel from his Definition of “kindness,” published in the international journal The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known:

It is…easy pompously to impose what we think is their desire on other people….To be kind, we must have the imagination arising from the knowledge of feelings had by others. This knowledge comes from the seeing of ourselves as like other people, while humbly recognizing that there is otherness, too.

Wanting to know the feelings of others is a vital aspect of what Aesthetic Realism explains is our deepest desire—to know and like the world, including the people in it. Managing unkindly, or imposing “what we think is their desire on other people” is a form of contempt, which Aesthetic Realism describes as the desire to get “an addition to self through the lessening of something else,” and shows is the greatest weakener of humanity—the cause of all injustice between individuals and among nations.

1. Some History

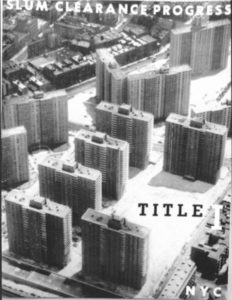

Jane Jacobs’ desire to understand what people in neighborhoods throughout New York City felt enabled her to write a book that criticized the biggest US planning policy of the 1950s and 60s, “slum clearance and urban renewal”—a policy that many people, including me, believe was based on contempt for people—and effectively end it.

This “urban renewal” consisted of entire city blocks—with walk-ups, brownstones, and apartment buildings, seen by officials and planners as old and derelict—being bulldozed and rebuilt with new, so-called “improved” modern high-rise residential buildings, with large areas of open, protected green space. But the people living in these neighborhoods were never asked if this is what they wanted.

Jane Jacobs saw and documented in her book that the very projects that were meant to revitalize the city took the life out of those neighborhoods, made them dull and lifeless. The large enclosed play areas were almost always empty. People who had lived on those blocks and moved out, having been promised new apartments, often could not afford those apartments and could not move back. Those who did move in felt cut off from all they had known, isolated in tall, sterile buildings lacking the sense of community they had experienced before. Jane Jacobs quotes a resident of a new development in East Harlem, in New York City, telling her:

Jane Jacobs saw and documented in her book that the very projects that were meant to revitalize the city took the life out of those neighborhoods, made them dull and lifeless. The large enclosed play areas were almost always empty. People who had lived on those blocks and moved out, having been promised new apartments, often could not afford those apartments and could not move back. Those who did move in felt cut off from all they had known, isolated in tall, sterile buildings lacking the sense of community they had experienced before. Jane Jacobs quotes a resident of a new development in East Harlem, in New York City, telling her:

Nobody cared what we wanted when they built this place. They threw our houses down and pushed us here and pushed our friends somewhere else. We don’t have a place around here to go get a cup of coffee or a newspaper even or borrow fifty cents. Nobody cared what we needed. But the big men come and look at that grass and say, “Isn’t it wonderful. Now the poor have everything.”

2. I Learn where the Fight between Managing and Understanding Begins

As I was beginning my career as a city planner in the 1970s, I saw this lack of desire to know what people felt, and also had it. I was aloof from the very people I felt I wanted to be useful to. Even as I had looked forward to the job, I became tired and bored at what I saw as endless community board meetings where I had to listen to people opposing what we were saying they should have. Hadn’t we in the central office already decided what this community needed?

Aesthetic Realism teaches that the most important thing in a person’s life is how we see the world itself, starting with how we see the first representatives of it we meet.

Growing up, I felt my parents, especially my father, made a great deal of me, and then seemed to dismiss me. Then, when my brother was born, I felt my dad preferred his son to me. I didn’t see it as funny when he’d jokingly say to me, “You’re my favorite daughter…because you’re my only daughter!” Many years later, in an Aesthetic Realism class, Eli Siegel would kindly, humorously ask me, “Well, if your father didn’t see his good fortune in having a daughter like you, can you put it down as his misfortune? Can you do that?” That had been the farthest thing from my mind.

It simply never occurred to me to want to know deeply who my father was. Instead, I regret very much that I set out to punish him in various ways. He was punctual, and so I made sure I was late for everything I could: coming to dinner, doing my weekend chores, leaving on a vacation trip. He’d begin by asking me to hurry up, and end by yelling. I said I’d change, but I never did.

Years later, in an Aesthetic Realism lesson, Mr. Siegel asked me: Do you think [your father] was afraid of your sense of satire?

Barbara Buehler: Yes, I think he was.

Eli Siegel: Now, if you were your father, what would you do [in response to that?]

Barbara Buehler: I’d want to stay away from her.

Eli Siegel: Which is exactly what he did?

Barbara Buehler: Yes, he did.

Seeing the hurtful choice to have contempt I’d been making was the beginning of a big change in my life. I began to want to know who Robert Buehler was, as a person—his love of baseball and ballroom dancing, his care for his business which he started from scratch as a young man with a friend, and how he met the woman he would marry. And at work, I began to listen to what people were hoping for, including at public hearings, where small homeowners and apartment dwellers were fighting for their communities—against a giant furniture store, a new sports stadium, a shopping mall. As I was more interested in knowing the feelings of people, I had a new respect for myself and also for my work as a city planner. And having studied the field of housing development that began in the early 1930s under the United States President Franklin Roosevelt and continues to the present, I have a conviction that housing is a basic right of every human being. In an Aesthetic Realism class some years ago, Chairman of Education Ellen Reiss asked me:

Do you think your work represents something deep in the self of every person, the desire to put together past and present, new and old?…And do you want to have as much feeling about the earth as you can?

The answer is Yes! And I’m proud that my colleagues and I have spoken at student conferences sponsored by colleges in the United States, on how, “Aesthetic Realism Explains the Cause of America’s Housing Crisis and the Solution!”

3. “An Instrument of What the Neighborhood Wanted to Do”

When Jane Jacobs’ book was published in 1961, it was an immediate success. I think people felt at last they were represented; they had a voice, someone wanted to understand how they felt. Her book also met virulent criticism from the planning and architectural establishment; also from many housing officials and politicians because a great deal of money for developers and builders was at stake. Her critics said she was condemning people to live in rundown buildings and relegating children to play in the streets. And she wasn’t even a planner! She didn’t have her degrees! How dare she criticize us! Who was this woman?

Jane Butzner Jacobs was born May 4, 1916 in central Pennsylvania. Her father was a physician and her mother a teacher and, later, a nurse. After high school, she attended business school and became a stenographer. Within two years, in the midst of the Great Depression, she came to New York to “seek her fortune.” She wrote in The Worlds of Jane Jacobs, Ideas That Matter: “I was unemployed a great deal too. I did a lot of wandering about the city in the course of job hunting.” During this time she wrote four articles for the American fashion magazine Vogue, on New York’s fur, diamond, flower, and leather districts, and “about manhole covers and what they told you about what was running underneath.”

In 1944 she met and married Robert Jacobs, an architect, who she said taught her how to read drawings, which would be invaluable in her work. They settled on Hudson Street in the West Village, a neighborhood in New York City of brownstones, row houses, and tree-lined streets where many of America’s noted writers, poets, and musicians lived. In the early ’50s she got a job writing for the magazine Architectural Forum and was assigned stories on city planning and rebuilding. As she went to these new developments, she felt there was something very wrong with this “renewal.” Where was the life, where were the people? In 1958, she wrote an article for Fortune Magazine on the development of urban downtowns which, along with her previous research and articles, became the basis for her 1961 book. In the chapter “The uses of sidewalks: assimilating children” she explained why the green grass-enclosed play areas were almost universally empty: because, from her observation, they were not interesting enough to children. She wrote:

…children have, and use, all manner of ways to exercise and amuse themselves. They slop in puddles, write with chalk, jump rope, roller skate, shoot marbles, trot out their possessions, converse, trade cards, play stoop ball, walk stilts, decorate soap-box scooters, dismember old baby carriages, climb on railings, run up and down….It is not in the nature of things to go somewhere formally to do [these activities] by plan, officially. Part of their charm is the accompanying sense of freedom to roam up and down the sidewalks.

A year after her book was published, New York City officials declared the West Village, her neighborhood, a slum, eligible for urban renewal. They picked the wrong neighborhood. Here is how the opposition to this plan was reported by Eric Larrabee in the summer 1962 issue of Horizon Magazine:

[On October 18, 1961,] when the New York City Planning Commission held a hearing at City Hall to announce that Mrs. Jacobs’ neighborhood had been designated a “blighted” area,…she and her fellow Villagers rose from the audience in such a manifestation of community wrath that police had to be called to clear the room.

She was labeled by city planners “as a sort of Madame Defarge—a character from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities—leading an aroused populace to the barricades.” “There seems to be a notion that I run these people,” she said. “But I wouldn’t have dreamed of telling them how to behave. I was an instrument of what the neighborhood wanted to do.”

Under her leadership, the community rallied day and night for over a year, finally defeating the 14-block urban renewal plan in 1969. The West Village—now recognized as one of the most beautiful residential neighborhoods in the city—was preserved and later designated a landmark district.

By 1970, wholesale government clearance of “poor” urban neighborhoods had been completely discredited in every major American city in the country. Historic preservation and respect for neighborhood scale and character, short blocks, mixed-use neighborhoods—all things she fought for—are today mandated practice, encouraged, protected and enforced by zoning.

4. Knowledge Triumphs Over the Desire to Run Things

In the prologue to his book James and the Children, Eli Siegel wrote:

If we are not interested in the feelings of others, in the feelings walking about as people walk, sitting as people sit, lying down as people lie down—we may either be deceived by them or be cruel to them.

At a pivotal time, Jane Jacobs wanted to be kind to people; she wanted to be interested in the feelings of others. It mattered to her that people lived in New York City, loved it, called it home.

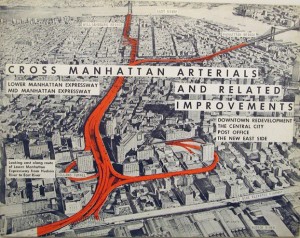

In 1968, city officials announced they would resurrect a 30-year-old plan, first proposed by Robert Moses, who, from 1924 to 1968, held some of the most powerful positions in New York State and New York City—at one point holding twelve positions at once. With this power, he did create beneficial public works, including many parks, playgrounds and civic centers. But he also forever changed the landscape of major parts of New York City by ramming through large-scale housing projects and decimating neighborhoods for major parkways and bridge approaches. Moses’s 30-year plan called for a vast 8-10 lane superhighway to be built where a 4-lane street ran through the heart of an area of the city now known as SoHo.

Moses had promoted this plan as a vastly practical way to connect the east and west sides of Lower Manhattan—allowing cars to speed across the island without the interference of pedestrians and street lights. There was no thought given to the quality and character of this area—and that people lived here! Renderings such as this were used to try and sell LOMEX, as it was called, to the public by lining it on the north with sleek glass office buildings. Requiring a 250- to 300-foot right-of-way, (which is almost the length of an American football field), it would have destroyed the distinctive neighborhoods of SoHo, today a landmark district with the largest number of 19th-century cast-iron buildings anywhere in the world; Little Italy, Chinatown, and Tribeca—today, also a landmarked district, wiping out 800 businesses and the homes of almost 2000 families.

Moses had promoted this plan as a vastly practical way to connect the east and west sides of Lower Manhattan—allowing cars to speed across the island without the interference of pedestrians and street lights. There was no thought given to the quality and character of this area—and that people lived here! Renderings such as this were used to try and sell LOMEX, as it was called, to the public by lining it on the north with sleek glass office buildings. Requiring a 250- to 300-foot right-of-way, (which is almost the length of an American football field), it would have destroyed the distinctive neighborhoods of SoHo, today a landmark district with the largest number of 19th-century cast-iron buildings anywhere in the world; Little Italy, Chinatown, and Tribeca—today, also a landmarked district, wiping out 800 businesses and the homes of almost 2000 families.

A crucial hearing was called by the New York State Department of Transportation to inform residents of the plan and distribute a pamphlet outlining its virtues. Jane Jacobs wrote later: “…The pamphlet, insofar as it touches upon the problems at all, dismisses them as not existing.”

New York State and City officials were intent on pushing this project through. Ms. Jacobs described how, as the hearing proceeded, questions from the audience were not being answered and tempers flared. Then a cry rose from the audience, “We want Jane! We want Jane!” and she proceeded to the microphone. “If the expressway is put through,” she said, “there will be anarchy.” A call went up for a march right then and there. A newspaper reporter [Leticia Kent in a Village Voice article] describes what then took place:

Elderly couples marched. Catholics and Jews. Italians and Russians. Businessmen and artists. They marched down the center aisle and onto the stage. The stenotypist grabbed her machine and the tape spilled out on the floor. Other marchers festooned the platform with tape and tore it into little pieces. “With no official record, there is no record,” Jane said. “There is no hearing. We are through with phony…hearings.” ‘Arrest that woman,” State Transportation Commissioner Toth ordered…“arrest that woman.” “I couldn’t be arrested in a better cause,” Jane said at the Clinton Street police station that night.

In 1969, New York City Mayor John Lindsay, seeing what he and other officials were up against, ended this plan for good.

The victory of understanding over the desire to run, manage, have contempt for other human beings is urgent for our world now. It is good will as Mr. Siegel defined it: “The desire to have something else stronger and more beautiful because this desire makes oneself stronger and more beautiful.” People in the United States, in Greece, and everywhere in the world deserve to learn this.

Barbara Buehler, associate city planner (ret.), worked in the Health & Social Services, Research Analysis, Education, Parks and Recreation Sections and Technical Review Division of the NYC Department of City Planning. She is an Aesthetic Realism associate, having studied in classes with Eli Siegel and currently in classes taught by Chairman of Education Ellen Reiss. This talk was originally presented at an Aesthetic Realism seminar.