Philip Guston: The Man, His Life, & His Work

By Dorothy Koppelman

I have been greatly affected by the work of Philip Guston and I think his drawings, his paintings, and what he says about himself can be a means of understanding some of the largest questions artists, and all people have about ourselves. As I look at the complexity, the changes, and to me, the most moving late works I see how true Aesthetic Realism is about the searching man, Philip Guston, and the depth of what he was after in his work; both are explained by the great principle, stated by the founder of Aesthetic Realism, Eli Siegel: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

Philip Guston was in a tangle his whole life between the two motions had by every person, and so grandly comprehended by Eli Siegel: the constant desire to respect the world—the intense, imaginative, relation of oneself and the world which is the source of all art—and that motion away from the world, a contempt for things in order to give oneself “a false glory” a superiority to, and a scorn for the very things that give us life. Contempt, “the addition to self through the lessening of something else,” is the enemy of art, and against life itself. Musa Guston Mayer quotes her father in her Night Studio:

“As a boy I would hide in the closet when the older brothers and sisters came with their families to mama’s apartment for the Sunday afternoon dinner visit. I felt safe. Hearing their talk about illnesses, marriages, and the problems of making a living, I felt my remoteness in the closet with the single light bulb. I read and drew in this private box. Some Sundays I even painted. I had given my dear Mama passionate instructions to lie…. ‘Where is Philip?’ I could hear them…. ‘Oh, he is away, with friends’….I was happy in my sanctuary.”

And, he continues: “After a lifetime, I still have never been able to escape….It is still a struggle to be hidden and feel strange—my favorite mood.”

This early preference for separation and deceit was uncriticized and never disavowed. Like a stone around the artist’s neck, it caused him to have at one time a depression, at other times frightening panics because Guston the artist knew that “innocent closet” wasn’t innocent, that hoping to fool people, and lying in order to hide, gave him the “false glory” of contempt, and he felt ashamed. Musa Mayer points out abundantly—and I admire the courage of her criticism—how her father wanted to be lionized at the same time as he wanted to keep himself hidden; basking in praise, going after the approval of people he could not see as comprehending his work; and how he disliked himself for doing so. He needed to hear the beautiful criticism I heard from Eli Siegel—it saved me from a divided life. He said in an Aesthetic Realism class:

The only time we are approved of in a manner we can approve of, and the only time we can approve of ourselves, is when we are just to things and to thought. Liking existence is the only honest basis for your self approval. The most important thing for you to do is see that in hoping to be affected by other things as fully as possible, you become more yourself.”

We Hope to See and Be Seen

In order to like ourselves we have to have an honest relation of seeing and being seen. What that means for an artist has immeasurable meaning. In my life, these two were separate. I wanted to look at things, yes, but I also wanted to hide; and I learned that my hope to be unseen curtailed my ability to see. Often when I was at a gathering and being pretty lively, I would suddenly want to go into a room by myself, and feel how good it was to be completely separate from other people.

In Philip Guston’s life there was always a battle, an unresolved battle. He was in a fight between being affected by other things and withdrawing into himself.

When he resigned from the Works Project Administration in the late l930s, having been, like many artists, engaged in doing paintings for public buildings, he said he wanted to “do more personal imagery.” But I think he felt the world was disorderly and he wanted in some way to go into hiding again. In paintings and drawings of the l940s like this painting of his wife and daughter, there is an excessive sweetness, insufficient depth of character. Was he himself sufficiently interested in the people he was looking at?

Porch No. 2 Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute Museum of Art, Utica, NY

Meanwhile, Guston, in his work, was critical of this desire to hide. A painting Guston saw as all about himself, he calls “Porch.” The figures turn their backs, cover eyes, and at the same time that broad cross, implying a window through which we see, criticizes the flat, deceitful surfaces of people and relates all those people trying to hide from one another to one another.

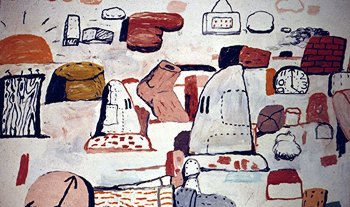

The paintings and drawings of Philip Guston affected people right from the beginning because in each of his very different ways of working—first as mainly a mural painter, later in his Abstract Expressionist paintings in which thick and thin paint, bright and dull colors, contrast and blending of shapes are the subject matter, to the final, moving “Thing” paintings with their weight and humor—the artist was dealing with the central opposites in our lives: separation and relation, ourselves as different from and the same as the actual Things, the colors, the shapes of the world around us.

Guston loved the work of Piero della Francesca, felt it had “serenity,” and as Robert Storrs notes in his Guston there is in the abstract paintings of the l950s a “pure pleasure in painting,” and yet one can see “an anguish manifested…”

I believe that Guston was trying to express in terms he later felt were too oblique, not clear enough, the conflict of being for and against reality itself—the fight between an off-pink, a muddy green, an ambiguous grey—all say something about the complexity of a person, the conflict of a self as assertive, a self hiding, being for things and against. But Philip Guston was not able to hide his own self-criticism by being obscure in either words or paint. Guston, as he shows in the video made and shown in the Woodstock Art Association exhibition of his l940s drawings and murals, is searching for something; at the same time he wants to be obscure, not plain, not simple. He is written of by his friends as not only studious but rebellious, contrary, argumentative, and not liking criticism.

What is in these sentences from the magnificent essay “Are Feelings Objects?—or, the Alienation of any Time,” by Eli Siegel could have changed that continuing torment Guston himself described: the fight between his hope to be separate from everything, and, on the other hand, his desire to be, to feel he was every object he saw. Mr. Siegel writes:

To see the outside world as the same stuff as our most secret or unknown thoughts is a fine necessity….There is a quality of murky grandeur we give ourselves in having our own feelings, recoiling, separate from other things….To feel that we can care for ourselves without seeing our feelings as objects, and liking them as objects, is to be wrong about our care for ourselves.

The greatest thing that ever happened in my life, and that can happen in any life, is hearing Eli Siegel’s aesthetic criticism of self. I thank again the destiny that has had that occur.

In an Aesthetic Realism lesson I had with Mr. Siegel shortly after I had begun my study, I told him that I felt there was a way I looked at things when I painted that was different from other times. As I walked down the street, for instance, I liked blurring what I felt were the harsh outlines of things. I liked being vague, making the outside world dim, and I didn’t even want to wear my glasses. He explained to me:

You don’t want to see things as they are because your ego would have to admit that things outside yourself are necessary for the self to be. You still have fun, as most people do, from manipulating things. That purpose is completely against art, and you cannot like yourself.

“If you do in time like things,” Mr. Siegel said so kindly,

you will like yourself. But there is that desire for separation where a person feels that in liking himself he has to hate other things, where he likes or goes for seeing the outside world, he lessens himself. This is the devil in two forms.

Mr. Siegel was criticizing the contempt in me that stopped me from liking myself and encouraging my greatest desire: to like the world. This criticism—and I verify this with half a century of experience and observation of people, including persons I have the honor to teach in Aesthetic Realism consultations—is the hope of humanity, and certainly of artists. I am proud to ask what Mr. Siegel asked me: “Do you want things to be confusing, and people to be bad so you can justify going into yourself and say it’s a devil’s world?”

Yes, I had that hope. Mr. Siegel taught me the difference between self-love and really liking myself. He asked me: “Do you prefer to have contempt and then glory in loneliness? Is that your plot?” And he gave this assignment to fight contempt:

Study your interior annulment machine. The best thing to do is get a Plotting Period each day, and write down what you plot. Then you won’t do it all the time. Ask yourself: What harm does being on two tracks do you? If this [being on two tracks] goes on, you’ll see 77% and then you’ll run to mama and hide your eyes.

You want to see sense in things and paint them, but then you feel it is a concession to the world to let things be as they are, to see them as there and yet mysterious—like you. It’s like putting moustaches on the Mona Lisa.