Henri Matisse—or, The Technique of Art & the Questions of Life:

What’s the Relation?

by Marcia Rackow

One of the big questions of life—and it was very big in my life—is how to resolve the conflict between independence and dependence. Like many women I prided myself on my independence and thought my power and distinction arose from feeling I could do things on my own. I once wrote: “We always consider those feelings of need and dependency as weak, degrading, demeaning and diminishing aspects of ourselves.” Yet I was also ashamed of the way I often acted helpless and meek, and excessively dependent. But I had no idea that this conflict, which troubled me so much, is solved in the technique of art. Mr. Siegel explained:

“The self has to be seen as the aesthetic oneness of independence and dependence. Aesthetic Realism believes that the more we proudly need the world, the more we are independent.”

When I began to study Aesthetic Realism with the consultation trio The Kindest Art, I learned that we can be proud of needing something if it is on behalf of greater like of reality—and this is what occurs in all art. We are rightly ashamed of our need of something if we use it against reality, for our own comfort and glory, which is contempt.

As a child I wanted to go to art classes, but my parents thought my “natural talent” might be spoiled. I got the notion early, and exploited it to the hilt, that I was special and that, as I once told my consultants, “I shouldn’t be touched by the outside world.” In college a professor wrote on one of my research papers: “It would have been good if you had quoted some other sources and critics in the field.” I felt if I read other opinions it would interfere with my own “brilliant” ideas. Meanwhile I felt increasingly separate from people and lonely.

My consultants saw that the way I flaunted my “independence” hurt my life and made me very unsure of myself. “People usually feel,” they explained, “I don’t need anything to be me.” “I’ve felt that,” I said, and was surprised when they asked me:

Consultants: “Do you need the floor, the chair?”

Marcia Rackow: “Yes!”

Consultants: “Van Gogh needed a chair not just to sit on but to express himself with. We have learned that art can teach us about need. A good painting, Aesthetic Realism says, is right about need.”

They assigned me to write about how the parts of a painting need each other; doing this opened up a new world. I wrote:

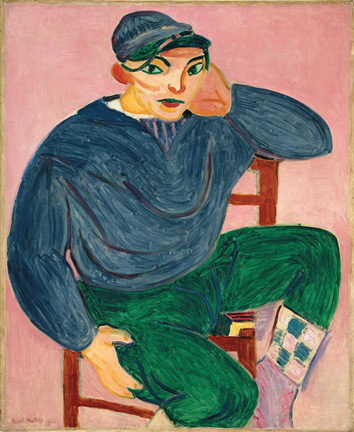

“Last night I had a marvelous experience looking at Matisse’s Young Sailor, II. I had never before seen what the relationship of the Sailor to the chair he is sitting on had to do with my life. Matisse put no limits on how much the young man would need the chair. The sailor and the chair share certain qualities—they are both vertical and horizontal, yet they are very different. By being related they enhance each other’s individuality and uniqueness. The slender, straight lines of the chair bring out the rotundity of the figure, and his curves enhance the firm, straightness of the chair.

“Last night I had a marvelous experience looking at Matisse’s Young Sailor, II. I had never before seen what the relationship of the Sailor to the chair he is sitting on had to do with my life. Matisse put no limits on how much the young man would need the chair. The sailor and the chair share certain qualities—they are both vertical and horizontal, yet they are very different. By being related they enhance each other’s individuality and uniqueness. The slender, straight lines of the chair bring out the rotundity of the figure, and his curves enhance the firm, straightness of the chair.

“The self‑contained, closed figure turning in on itself is interrupted, opened up, and lifted by the strong but delicate chair and soft open ground. The pink space which contrasts so dramatically with the blue and green of his costume brings out the vividness and strength of his form. As the sailor, the chair, and the ground become locked together, the more they become distinctly what they are. The more they are dependent, the more they are independent.”

This was a tremendous turning point for me because, as I told my consultants, “art came down off the walls and into my life.” I am unboundedly grateful to have learned that art is not an escape from reality, but a means of seeing it truly: “All beauty,” Eli Siegel stated in this great principle, “is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

I am grateful to Mr. Siegel for enabling me to change from a person who was aloof and separate to a woman whose life is rich and happy and wide, and whose mind and heart are fuller, more alive than would ever have been possible.

I have seen, and see more every day, that I need the world and other people to be myself. Aesthetic Realism revolutionized how I see everything, including men. I once felt I needed my father for importance and solace, and thought that is what other men should provide. And now in my marriage to filmmaker and Aesthetic Realism Consultant Ken Kimmelman, I am proud to need a man to see everything better! His love for film and his important work in his field have added so much to my life. And his care for art has encouraged me as artist and teacher. His lively, kind good humor, his criticism of me, have enabled me to be in a better relation to people and the world.

I. An Artist Is Proud to Need the World

“Every artist,” wrote Dorothy Koppelman in the book We Have Been There,

“is proud to need the brush he uses, the canvas he paints on, and proud of his need for every object he sees. He is proud to be incomplete and glad the world exists for him to become more and more complete.”

Henri Matisse, one of the great painters of the 20th century, shows we need to be affected by the world—to see things freshly in order to really express and be ourselves. He wrote:

“The effort needed to see things without distortion takes something very like courage and this courage is essential to the artist, who has to look at everything as though he saw it for the first time…If he loses that faculty, he cannot express himself in an original, that is, personal way.”

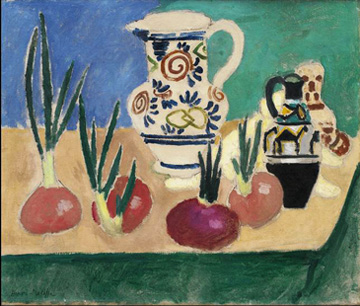

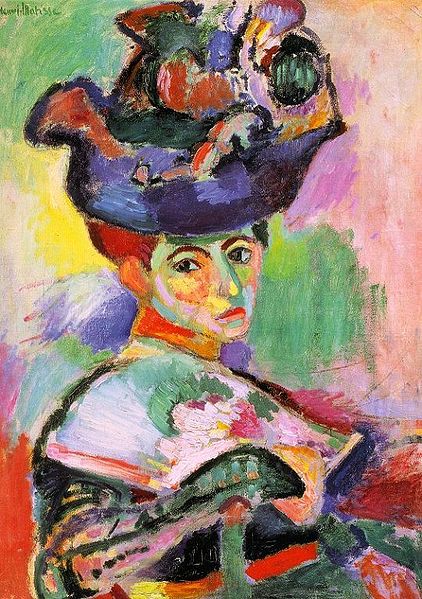

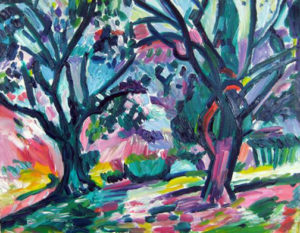

Henri Matisse brought a new freedom to color beginning with Fauvism in 1905—

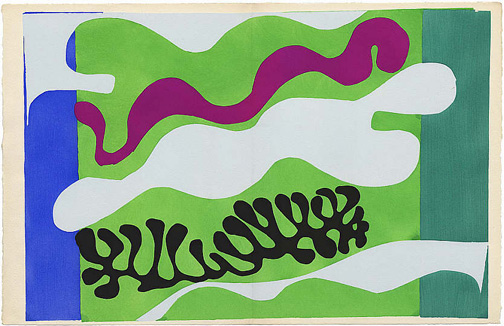

and this continued throughout his long career, culminating in his revolutionary paper cut-outs, which he did in the last years of his life.

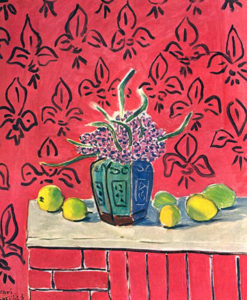

Matisse needed the Mediterranean sea—what he called “that light”—to free his vision. These paintings scandalized Paris in1906, and led the critic Vauxcelles to call him and his colleagues “The Fauves”—the Wild Beasts.

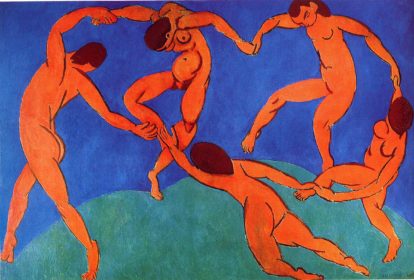

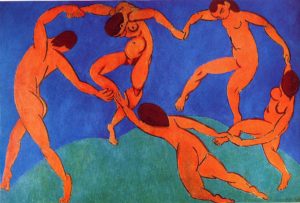

Matisse needed color—”a beautiful blue for the sky, the bluest of blues, a like green for the earth, and a vibrant vermilion for the bodies” to come to this joyous expression—his “luminous harmony.”

II. Art Puts Together Inside & Outside—As People Need To

Women have felt that needing the world is equivalent to slavery and what they do need is their privacy—their secret thoughts. In a class Mr. Siegel criticized this false notion of freedom in me. He showed me how much I valued my secrecy. He said, “The question is how much are you a part of general truth? How much do you want to be in relation to things and to the world?”

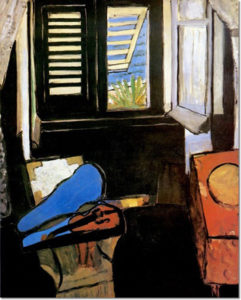

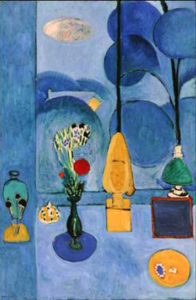

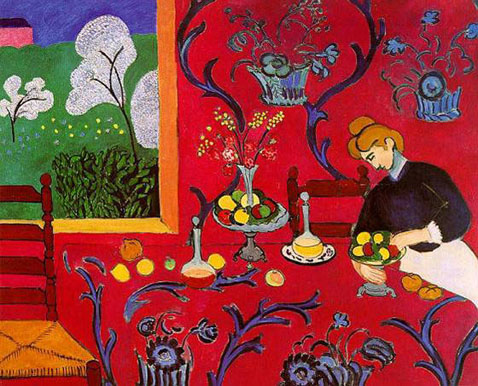

A central theme in Matisse’s work is relation—represented by the Open Window. We see that motif throughout his career, beginning in his earliest works.

He shows how inside and outside are continuous. Rooms have stood for the self, and a window for our possibility of looking out, and of the outside world coming in. Matisse said:

“The space is one from the horizon to the interior of my workroom and the boat that passes lives in the same space as the familiar objects around me, and the wall of the window does not create two different worlds.”

Inside and outside have been seen as in two different worlds, and women have been political with these opposites.

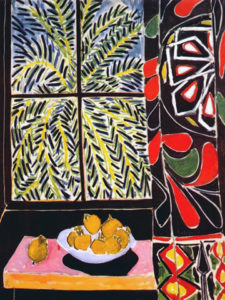

In this surprising painting, Interior with Egyptian Curtain, 1948, done when Matisse was 80, inside and outside are thrillingly, vividly in one world.That radiant palm tree with its bright yellow branches and brilliant black and green leaves against the blue sky fills the entire window and seems to be bursting into the room. Inside the room is that wild black Egyptian curtain with its big pinwheel design and its brilliant red and green leaf forms dancing around the center. It curves gracefully over the pink table with a white bowl of orange pomegranates, so jaunty that one seems to have bounced out of the bowl.

In this surprising painting, Interior with Egyptian Curtain, 1948, done when Matisse was 80, inside and outside are thrillingly, vividly in one world.That radiant palm tree with its bright yellow branches and brilliant black and green leaves against the blue sky fills the entire window and seems to be bursting into the room. Inside the room is that wild black Egyptian curtain with its big pinwheel design and its brilliant red and green leaf forms dancing around the center. It curves gracefully over the pink table with a white bowl of orange pomegranates, so jaunty that one seems to have bounced out of the bowl.

“Line and color,” Mr. Siegel wrote, “represent without and within and these are of our very selves. These are the fate of ourselves, and a problem which is of reality and which is of people, is dealt with by the artist.”

The question of inside and outside has affected women deeply. They’ve felt what is outside of their homes is in competition with their cozy private world, and have also felt they would be less in needing that outside world.

But is this curtain made lighter, more vibrant through its relation to the dazzling palm and are both richer, warmer, softer through the presence of the pink table with pomegranates? Cover either and see if they are more or less. A woman can feel that her inner life, her “interior,” is the most vivid, dramatic, exciting thing in the world and other people’s feelings couldn’t add to her. Here the stark, turbulent pattern of the curtain and the more tranquil table with fruit are like aspects of ourselves—sweetly in the sunlight and darkly swirling. Instead of being in separate parts of our minds and hidden within, Matisse shows how curtain and table are related to and need the energetic and sunny palm outside.

Yet the man who wanted to throw open the windows and whose work is so ebullient and expansive, was in his everyday life, very reserved. His friend, the writer Louis Aragon, said he “rarely revealed what was going on within him.” Matisse himself wrote:

“I express…what moved me in nature, through the empathy I created between the objects that surrounded me,…and into which I succeeded in pouring my feelings of tenderness without risking to suffer from doing so as in life.”

“I express…what moved me in nature, through the empathy I created between the objects that surrounded me,…and into which I succeeded in pouring my feelings of tenderness without risking to suffer from doing so as in life.”

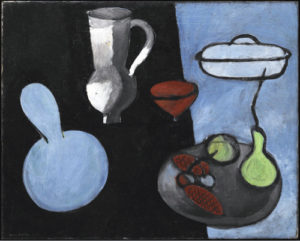

While I think Henri Matisse had an authentic fear of not being understood, he also likely had a suspicion of people that had some superiority and contempt in it. His theme of the window, and his life‑long study of the relation of color and outline answer technically the problem he had as self—to make a one of inside and outside, to be proud, as person, of needing the outside world he so gloriously felt he needed as artist. In The Right Of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, Mr. Siegel explains:

“In aesthetics, there is an answer to the questions that don’t seem aesthetic at all. The making one of color and outline in art is an aesthetic job; but it is similar to the job we all have of being controlled and spontaneous at once; orderly and responsive at once.”

How much Matisse was critical of his reserve and wanted to counter it, I think is in the fact that his color was intense—so outward. Mr. Siegel once said, “In Matisse, the color almost shows a rejection of the outline, the color is so strong.”

III. Are We Less Independent Needing People? Art Says Resoundingly, No!

As artist Henri Matisse felt he needed people for his expression:

“What interests me most,” he said, “is the human figure. It is through it that I best succeed in expressing the nearly religious feeling that I have towards life…that deep gravity which persists in every human being.”

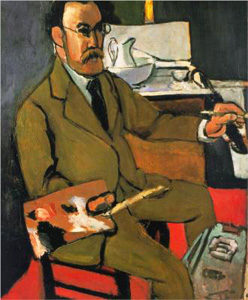

These are some of the paintings he did over fifty years studying the human figure.

Wrote the critic Gelett Burgess: “His paintings do have life!…They are not merely models posing, they are human beings with souls.”

And in his many paintings of his wife, Amelie, whom François Gillot described as a “woman with mind,” whose “flair for new ideas” encouraged him, we feel Matisse tried to show that “deep gravity.”

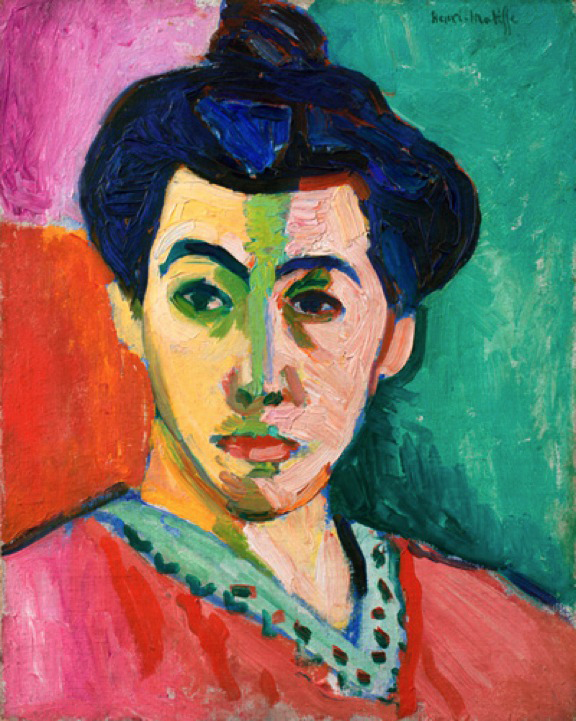

In this landmark painting of 1905, The Green Line, there is a stunning relation of outline and color that outraged Paris, but also changed modern painting.

With all its brilliant color, there is tremendous sobriety, containment and depth in this painting. That shocking green line down the center of her face is so outward, but its jarring cool color brings out the depth of her dark eyes, and relates her to the green space behind her. Matisse once described his wife as that “sweet, petulant partner.” I think her sweetness, and the petulance, which it seems he was critical of, are in relation as he composed the pinks and reds with the cool, even acidy greens and the dark rich blues and blacks. Matisse was trying to give form to two aspects of his wife he likely had a hard time making sense of.

IV. A Woman Learns about Proud Need

“According to Aesthetic Realism,” Mr. Siegel writes in Self and World,

“the self is trying to come into composition with the world, and at the same time be different, individual, separate, free….The fact that we need the world does not mean that we are not free; for when we need something to be free, the need is not disabling.”

These sentences describe the study that is changing women’s lives in Aesthetic Realism consultations. Jeanette Winfield, an energetic and serious woman, who works as a children’s librarian on Long Island and is divorced from her husband, told us that she wanted “a better way of looking at my life” and that she had a “struggle with bitterness.” When we asked what she was most bitter about, she said, “That Jerry left me after 20 years of marriage.” She told us:

“I was dependent on my husband. I felt safe. Jerry was brilliant. There was nothing he couldn’t do. When he wanted to get his degree to teach comparative literature, he did it. I looked up to him. I depended on him to take care of the finances, everything.”

She also told us she and her husband studied the literature of Romanticism, and worked for justice together by opposing the Vietnam War. We saw that she was in a terrific mix‑up about a need for her husband she could be honestly proud of and a need she was ashamed of. She told us that growing up she was “the one in the family who was seen as knowing everything.” I told her that Mr. Siegel once described this hurtful attitude in me. He said: “As soon as you saw a man, you had to show you were smarter.” We asked:

Consultants: “Do you want to see clearly what Jerry Winfield felt? Do you think your attitude of superiority may have stopped him from showing his feelings?”

Ms. Winfield said yes, thoughtfully. And she told us,

“When he left, he said in a rage, sarcastically: ‘You always acted as if you were better than me.’ “I’m beginning to see the seeds of good and bad in the marriage,” she said, “and that is encouraging.”

As she is reconsidering how she saw her husband, she feels truly proud and respects herself. She feels her life is coming into a better “composition with the world,” and she is freer, more hopeful about the future.

V. Our Greatest Need

“Aesthetic Realism,” Mr. Siegel wrote,

“does say that the thing most needed by [a person] to have a like of himself or respect for himself that is valid, is the feeling that the world is seen by him in a fair way, an accurate way, and one that goes towards, as much as possible, liking the world.”

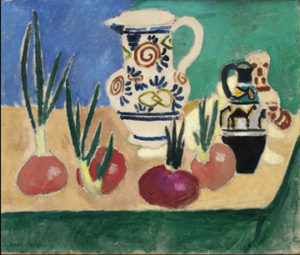

In his art Henri Matisse was proud to need the world, including the many objects that appeared over the years in his paintings. He wrote as a caption to a photograph: “Objects which have been of use to me nearly all my life.”

In 1941, despite a grave illness and the terrors of war, there was a new flowering in his work—his glorious cut-outs.

Though he was offered a safe home in America, he refused to leave France, and his wife and children worked courageously in the Resistance. Wrote Louis Aragon during the war, “At the darkest point in our night, they will say he made those luminous drawings.”

Though he was offered a safe home in America, he refused to leave France, and his wife and children worked courageously in the Resistance. Wrote Louis Aragon during the war, “At the darkest point in our night, they will say he made those luminous drawings.”

“A need,” Mr. Siegel writes, “is seen by Aesthetic Realism as anything a person is nearer to completeness with.” His own love for reality in all its forms—his proud need of it—made for the beauty and grandeur of Aesthetic Realism. It is the knowledge every person on this earth needs and deserves to know!

Related Articles:

The Joyous Drama of Outline and Color: Icarus by Henri Matisse by Marcia Rackow

Matisse’s The Blue Window; or, The Self Is Both Inside & Outside by Barbara McClung

Vermeer’s Young Woman with a Water Pitcher—and What Men and Women Are Hoping for in Marriage by Julie and Robert Jensen