POWER AND TENDERNESS IN MEN AND IN PICASSO’S MINOTAUROMACHY

By Chaim Koppelman

Reprinted from the Journal of the Print World

Every time I am stirred by and study the meaning of an artist’s work I am more grateful for my study of the philosophy of Aesthetic Realism with the great American poet and critic Eli Siegel.

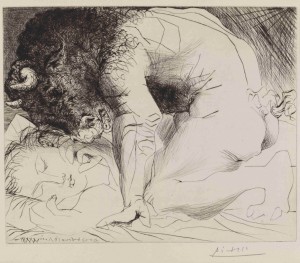

He defined beauty for the first time and showed how art answers the questions of our lives. “All beauty,” he stated, “is a making one of opposites and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” This historic and kind principle explains what impelled Picasso in his etching masterpiece and why people are deeply affected by it. Power and tenderness, opposites that so often fight in men, are made one beautifully, richly, movingly both in subject matter and technique in Picasso’s 1935 allegory, the Minotauromachy.

Opposing Forces in Us

The centaur, the satyr, and most importantly the minotaur—a oneness of man and bull—appear increasingly in Picasso’s etchings of the 1930s. These beings represent the duality in all men and in the artist himself; the opposing forces he wanted to put together as person and as artist.

The critic Anthony Blunt describes Picasso’s use of the minotaur as at times “a symbol of violence and brutality, as in the scenes in which it is about to rape a sleeping girl … at other moments it is gentle and domesticated.” The painter Francoise Gilot, who lived with Picasso for almost ten years, describes his “extraordinary gentleness.” But about a three-month separation she writes, “I didn’t enjoy seeing (his greatness) cheapened by a kind of imperialism which I thought incompatible with true greatness.”

Picasso, whose Guernica shows his hate of fascism, could be an imperialist with women; and I believe this attitude troubled him, as it does all men. Aesthetic Realism says clearly: domestic “imperialism,” and the ultimate tyranny of fascism both arise from contempt: The addition to self through the lessening of something else. 1

Respect and contempt are crucial opposites in the life of man. The power of respect is always kind, and the ugly power of contempt — the desire to have our way, to make less of everything not ourselves — is always cruel, against art and life.

The Chief Thing We Have Suppressed

In his mighty essay, “The Suppression of Good Will,” Eli Siegel writes: “The chief thing man has suppressed so far is his good will. This, perhaps, is the largest matter in human history.” And this “good will in man … struggling to come forth” literally describes the yearning expressions of so many of Picasso’s minotaurs. They yearn to be kinder, more human. The minotaur is every man.

Here, the minotaur lunges towards a young girl who holds flowers in one hand and a candle in the other. Upright and unafraid to look—the only figure in the print whose legs have one firm direction—she has the power to meet the minotaur because she has good will. She wants to see him, wants him to find his way into the light. She, with her guiding candle, and the onrushing minotaur in their great contrast complete one another. The arm of the beast seems to push away and yet go towards the light. The young girl, representing tenderness and the brave desire to see, and the bull-man with his raw power and the groping desire to see join in the continuous form of an arch. Two aspects of the self are joined and it is thrilling.

Here, the minotaur lunges towards a young girl who holds flowers in one hand and a candle in the other. Upright and unafraid to look—the only figure in the print whose legs have one firm direction—she has the power to meet the minotaur because she has good will. She wants to see him, wants him to find his way into the light. She, with her guiding candle, and the onrushing minotaur in their great contrast complete one another. The arm of the beast seems to push away and yet go towards the light. The young girl, representing tenderness and the brave desire to see, and the bull-man with his raw power and the groping desire to see join in the continuous form of an arch. Two aspects of the self are joined and it is thrilling.

In his essay “Husbands and Poems,” Mr. Siegel describes an everyday conflict: “When men are energetic, forceful (or worse), they lack sensibility, a fine understanding, rich sympathy; when they are gentle, sentimental, soft, they no longer seem to have strength, energy, momentum.” In Aesthetic Realism classes with Mr. Siegel I was seen the way all men hope to be seen—as wanting to have my way and also be kind. I learned what I had to do both as artist and husband—put opposites together. Good will in life, he taught, is, like aesthetics, a oneness of opposites. He described the rift I felt: “We have our fierce self and our yielding self and they are not seen as one,” and he suggested I imagine my wife sitting in the audience of a large theatre, point to her and say, “Here is a woman I want to be kind to.”

Good Will Has Power and Delicacy

Good will, like the technique of etching, is a oneness of power and delicacy. The finest line scratched on a surface is bitten into the plate by a powerful acid. The massive head of the minotaur is a collection of incisive and delicately drawn lines; its force comes from a oneness of energy and precision; critical exactitude for the kind purpose of showing the minotaur as he truly is.

Aesthetic Realism states that good will must include criticism of all forms of contempt. Picasso, in this print, is critical of people going after false power by dismissing things, trying to conquer them, not wanting to see conflict in ourselves. The man on the left climbing the ladder is ethically dual. He turns his back on the moral drama and yet faces it. His feet are flabby. He seems cowardly, but, like the minotaur, he wants to see.

Are the two women with their turtle doves in the window above trying to see, be in a superior position, or both? Is the artist critical of double motives when he encloses them in a stony niche as he places the minotaur, with all his brutishness and groping, free in open space?

Why does the artist place the picador on her horse between the minotaur and the girl? I believe Picasso’s criticism of himself, the way men use their strength to have their way, how women use their bodies to conquer men is the subject of many of his prints. Here, the bare-breasted woman picador holding her sword and draped brokenly over the horse has failed in her purpose to conquer the minotaur through body alone because the minotaur, even as he shields his eyes from the light, wants what the young girl and the light represent. He wants to see, to know, to feel, to be kind. The bull aspect of himself alone does not satisfy him. He wants power and tenderness together, body and thoughtful seeing together.

Picasso’s etching affirms Aesthetic Realism; the only power that will satisfy a man is the power of good will. Mr. Siegel had that power always. It moves me that the Minotauromachy hung in the room where, for four decades, he lectured so magnificently and where I had the lessons that so beautifully changed my life. This education which goes on now at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation in New York is making men and women honestly kind and it can change America.

Chaim Koppelman (1920 – 2009) was one of the earliest artists to see the value, for both art and life, of the philosophy Aesthetic Realism. He began to study with its founder, the poet and critic Eli Siegel, in the 1940s, and was on the faculty of the School of Visual Arts and the Aesthetic Realism Foundation for many years. In 2011 the Museo Napoleonico in Rome, Italy had a major show of his work titled “Napoleon Entering New York: Chaim Koppelman and the Emperor.”

1Eli Siegel, The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, issue no. 1114, “What Contempt Is and Is Not.”