What Happens in an Aesthetic Realism Consultation?

What Happens in an Aesthetic Realism Consultation?

by Margot Carpenter

The education taking place in Aesthetic Realism consultations is new in the understanding of people’s lives. It brings comprehensiveness and dignity to the issues people are puzzled by, distressed by, and trying to make sense of every day. It shows that the questions of people’s lives are aesthetic questions, answered in outline by the art of the world. As Aesthetic Realism consultants speak to a person in a consultation, everything we say in the consultation is based on the following principles stated by Eli Siegel:

- Every person is always trying to put together opposites in himself or herself.

- The deepest desire of every person is to like the world on an honest or accurate basis.

- The greatest danger or temptation of a person is to get a false importance or glory from the lessening of things not oneself; which lessening is Contempt.

- The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites.

It was in classes and Aesthetic Realism lessons conducted by Mr. Siegel that I first began to learn these principles. Consultations are given by three consultants so that the knowledge and experience of each adds to that of the others. In this way, there is less chance of something central being missed as we try to understand and be fair to every aspect of the person having consultations. What is the practical use of the principles I quoted? That is a question I see answered daily by the facts and lives of the women who study Aesthetic Realism with The Three Persons, the consultation trio with which I have taught since 1971.

A Young Woman and the World

For instance, there is Hope de Renza,* an executive secretary at an international bank. Early in a first consultation, a person is often asked this kind question, which Mr. Siegel asked in Aesthetic Realism lessons: “What do you have most against yourself?” Ms. de Renza told us, “I find myself cold sometimes and angry. I have a lot of dislikes….I really don’t know me that well.”

The Three Persons: What is the thing that makes you angriest?

Hope de Renza: I really don’t know. I want to be happy, but I’m not.

The Three Persons: Aesthetic Realism teaches that every person has an attitude to the whole world, and that the way we see the world begins early. Do you think the world is friendly to you or not friendly?

Hope de Renza: I think it’s friendly.

The Three Persons: Do you think a person who sees the world as friendly is cold to it or warm to it?

Ms. de Renza smiled, but did not reply.

The Three Persons: Would you like to be warmer to the world? Do you think that’s why you smile?

Hope de Renza: Yes.

The Three Persons: But is all of you behind the smile?

Hope de Renza: Probably not.

The Three Persons: That is something to be gone after, because otherwise we feel we have a self inside that nobody sees.

Inside and Outside

We asked Hope de Renza to read this principle:

“Every person is always trying to put together opposites in himself or herself.”

The Three Persons: While you go out in the world, go to work, meet people, do you feel there is something in you that has never been in circulation, never been seen by anybody?

Hope de Renza: Yes. I know there is.

The Three Persons: Is a world you see as friendly a world you would show yourself to?

Hope de Renza: Yes.

We were talking with Hope de Renza about opposites: self and world; and also inside and outside—what she felt within, to herself, and what she showed outwardly. These opposites of inside and outside are big in every person’s life, though every person has them somewhat differently. A question Mr. Siegel asked me in my first Aesthetic Realism lesson is about them—and has within it the pain that had been in my life and the large change which has happened in me. “What do you want to depend on,” he asked me, “who you are, or how pleasing you can make yourself?”

When I began to see that the opposites in me were also in the things around me, I felt immediately more connected to the world. I liked it more. We asked Hope de Renza to look at the objects on the table we were sitting at. The notebooks we were taking notes in, different pens and a pencil, a tape recorder, a cassette case, and the wooden table itself—each had an inside and an outside. As we spoke about each item, I saw Ms. de Renza’s dark eyes get brighter with interest. We asked: “What do you think of how inside and outside are working in this tape recorder?” She leaned forward.

Hope de Renza: Well, the inside is protected as it’s recording.

The Three Persons: Is this somewhat the way our insides are protected by our skin—which is part of our appearance?

Hope de Renza: Yes.

The Three Persons: Meanwhile, we can look nice while we harbor not so nice thoughts. Do you ever do that?

Hope de Renza: Yes, my friends tell me I’ve got a happy-go-lucky personality, but sometimes I can’t wait to get home by myself. I can smile as I’m thinking, “I can’t wait to get out of here.”

The Three Persons: Does the tape recorder do that?

Hope de Renza: No, I don’t think so. Doesn’t it just take down what’s said?

The Three Persons: As far as we know it does. Its insides are protected, but not for the purpose of having itself secretly to itself. Do you think then, the tape recorder has the opposites of inside and outside working as one?

Hope de Renza: Yes.

The Three Persons: If inside and outside can work well in the tape recorder, can you learn something from it?

Hope de Renza: This is amazing. As we begin to see that we and the world have a structure in common, and that the opposites in reality are the same opposites that are in us, the world looks warmer, less uncaring and hostile, more friendly than before. And we feel that the rift we have made between these opposites is not inevitable.

The Aesthetic Criticism of Self

In his book Self and World: An Explanation of Aesthetic Realism, Eli Siegel writes:

The basis of the Aesthetic Realism method is that every human being is a self whose fundamental and constant purpose is to be at one with reality. It is impossible for that self to evade this purpose, although he can curtail it, obscure it, limit it.

Aesthetic Realism consultations are critical, because a person wants and—in order to like herself—needs to understand how she has “curtailed, obscured, limited” her own desire to like the world. The great, crippling interference from within ourselves with our desire to like the world, Aesthetic Realism explains, is our simultaneous desire to have contempt . Eli Siegel described contempt in the following principle: “There is a disposition in every person to think we will be for ourselves by making less of the outside world.” He was the person in the history of thought to identify contempt as the fundamental interference with people’s minds, and to see the tremendous harmfulness of it in both its most ordinary forms and most extreme.

In over three decades of giving consultations, I have seen his description of contempt as “the great failure of man” to be true in countless ways. Sometimes the way a person we are speaking to has cultivated contempt is unique, but always its beginnings are those I have learned to recognize in myself. As I criticize contempt in another person, I am criticizing it in myself. This is one of the greatest benefits to me personally as an Aesthetic Realism consultant.

In the instance of Ms. de Renza, we spoke about what she called “my private world to myself inside,” and how, though she had a busy social life, she felt bored and apart from people. And as often happens, I was able to ask questions which in a lesson, Mr. Siegel once had asked me. Ms. de Renza, like most people, felt lonely. We asked:

The Three Persons: Somewhere, do you feel you’re too good for people?

Hope de Renza: I don’t think so.

The Three Persons: Do you feel people deserve for you to show yourself—just as you are, all the time—to them?

Hope de Renza: I see what you mean. No, I don’t.

I remember telling people I knew, shortly after I had begun to study Aesthetic Realism how much it affected me to learn that a self is criticized on the same basis a poem is: how well it puts opposites together and how fair it is to a subject, the central subject being reality itself. I immediately felt my life had been given scope, and a dignity I had never felt before. The years and every person we have spoken to in consultations have ratified this feeling.

In this consultation, we asked Hope de Renza to read a poem, written in 1864, which Eli Siegel saw as very important: “Who Shall Deliver Me?” by Christina Rossetti. He read it in some of the earliest Aesthetic Realism lessons he gave, in the 1940s, and it is often part of consultations now. As she read these stanzas, Hope de Renza told us, “This describes what I feel”:

All others are outside myself;

I lock my door and bar them out

The turmoil, tedium, gad-about.

I lock my door upon myself,

And bar them out; but who shall wall

Self from myself, most loathed of all?

When a woman sees that what she feels was felt by another person over a hundred years ago, and is told that many other people—women and men—reading this poem in Aesthetic Realism consultations have said, as she did, “This is what I feel,” a certain loneliness and sense of separation leave her. When we see that the feelings of other people are more like our own than we thought, we do not have contempt for people in the taken-for-granted way we did before. Contempt dies hard, and we need to look in an ongoing way at our desire to have it, but the initial thing which can begin to oppose our contempt is seeing that other people’s feelings have the same reality as our own.

The Opposites Illuminate Any Situation

Aesthetic Realism is for all people. In 1972, Eli Siegel composed this “Poem for Consultants”:

Unheard, inward disaster;

Knowledge of this

Is what we’re after.

In the instance of Hope de Renza, the disaster was “unheard, inward.” She didn’t like the world which made her and into which she had come. She is learning from Aesthetic Realism, as I learned, that in not liking the world, she has been working against her own deepest hope.

But as might be expected in the study of people and of mind, consultations have also been exceedingly dramatic. An incident will be told, and I will ask myself, “What does this mean?” “What opposites are here?” Every time, the opposites illuminate the situation.

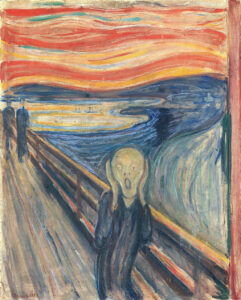

Take, for example, a consultation with Carla Buhrman,* a traffic manager. First there was a discussion of the work of an artist she cares for, Edvard Munch—a surprising choice for a woman who spoke in a kind of monotone a good deal of the time, and gave the appearance of being bored. In much of Munch’s work, the terror, the angles of people, the screams inside of people as they are near each other, but seem to feel separate, are presented.

We asked Ms. Buhrman, “Is there something in you like the terror you can see in Munch’s work, in the people?” “Yes,” she replied. “Is something of that terror in you all the time?” “Yes.” We began to show her that Munch does not cover over people’s trouble with dullness, as she had tried to do. He shows there is a composition to things which is beautiful, even while there are situations and feelings one doesn’t like. (See an article about the work of Edvard Munch by the noted artist and printmaker Chaim Koppelman.)

Later in the consultation, Carla Buhrman told us about an incident that occurred when she was about four years old. Her parents were having a patio party, and she dropped a glass on the patio stone floor. It shattered to bits. “I looked down at the shattered pieces of glass and got terrified. I ran away for blocks before someone could stop me,” Ms. Buhrman told us, and as she did, we could see the feeling had not entirely gone. Certainly a child can fear being punished for breaking a glass, but Ms. Buhrman’s fear seemed to be about the broken glass itself.

We asked many questions, and I was very moved by what emerged. A glass is smooth—Carla Buhrman likes to appear calm, almost smooth. And we learned that beginning very early she was mixed up about smoothness in other people. She felt people could seem nice, pleasant, and then be quite different—angry and even mean, she said:

Carla Buhrman: They would act very warm, and then be cold, uncaring.

Ms. Buhrman had a notion early of the world around her as being smooth and then rough, warm and then cold. It didn’t make sense. Her notion of the world was fragmented.

The Three Persons: Do you think when you saw the shattered glass, it was an illustration of an idea of the world which was one you’d already had, a world you couldn’t like?

Carla Buhrman: I feel this is so important. Yes.

The Three Persons: Aesthetic Realism explains that we need to feel the opposites in the world can make sense. They can, and we can learn to see how they do. You were running away from the picture of a shattered world.

Carla Buhrman: I think that is true. That’s what I felt.

The Three Persons: Meanwhile, the work of Munch, which you care for, presents the feeling people are breaking apart, with form and composition that we feel is beautiful, as in “The Scream.” This shows that the opposites which so can trouble us, can be composed, can be one.

In consultations, I see people, like Hope de Renza and Carla Buhrman, feel their very selves are understood. This is because Eli Siegel, with his vast scholarship, never tired of asking about people, as he did in his poem “Ralph Isham: 1756 and Later”:

What was he to himself?

There, there is something.

That is what Aesthetic Realism has taught consultants to ask. When Aesthetic Realism consultations began in 1971, Mr. Siegel said that the motto for consultants should be this line from Chaucer: “And gladly wolde he lerne and gladly teche.” Consultants and Associates are learning as we attend classes conducted by Chair of Education Ellen Reiss, who was appointed by Eli Siegel. Part of our education is the opportunity to hear aesthetic criticism. As people living our own lives and as consultants trying to meet the hopes of others, we are still learning about ourselves. I think the way Aesthetic Realism explains reality is true, and it is beautiful. I am grateful to the women we teach for enabling me to see that freshly in every consultation.

*The names of persons having consultations have been changed.

Return to Consultations homepage