Aesthetic Realism Foundation

141 Greene Street

![]() New York, NY 10012

New York, NY 10012

Autumn 2022

Dear Friend,

Meryl Nietsch-Cooperman is an Aesthetic Realism Consultant, and a teacher—with Barbara Allen and Devorah Tarrow—of the Understanding Marriage! class.

At this time of so much worry in the world, I am writing to you about what I consider the most important, truly hopeful, vitally needed education there is: Aesthetic Realism, founded in 1941 by the great American poet, critic, and philosopher Eli Siegel.

MERYL NIETSCH-COOPERMAN is an Aesthetic Realism Consultant, and a teacher—with Barbara Allen and Devorah Tarrow—of the Understanding Marriage! class.

Aesthetic Realism explains, for example, the cause of racism, and what can finally end racism in all its cruelty. Aesthetic Realism makes clear the large cause of trouble in the US economy, and what a just economy is. It is the means of understanding—and changing—the way of mind behind the horrific mass shootings that have become so frequent in America. Aesthetic Realism explains mightily, too, our own personal questions, confusions, hopes. It has the understanding of what love is, how to have true confidence, how we can honestly like ourselves, and how to make sense of a world that has both terror and beauty.

I am Meryl Nietsch-Cooperman, an Aesthetic Realism consultant. For many years I have seen that Aesthetic Realism is true, and I’ve seen its tremendous usefulness for everyone.

To illustrate the importance of this foundation and the knowledge it presents, I’ll begin with an article by Aesthetic Realism consultant Robert Murphy. Had what is said in it been widely known and studied after it was published over twenty years ago, we would certainly have a more humane nation. The article appeared, among other places, in the San Antonio Register—and San Antonio is very near Uvalde, Texas, where children and teachers were shot to death in their school this year. Here is the article, in a somewhat condensed form:

Why Young Men Are Bored & Angry

by robert murphy

As the school year is underway, parents, teachers, and students are terrified of the anger that has erupted into school shootings.

I know—and I feel this with the depths of my being—that the scientific, terrifically kind education of Aesthetic Realism can have the out-of-control anger in young people that caused tragic deaths end. I make this statement carefully, after over 25 years as an Aesthetic Realism consultant teaching young men between the ages of 10 and 21, with my colleagues.

Aesthetic Realism makes clear the beginning fight in the mind of persons of any age: between wanting to like the world, see meaning in it—which is the deepest desire of all of us—and the hope to find the world contemptible and so feel superior to everything. Aesthetic Realism defines contempt as “the addition to self through the lessening of something else.” Contempt is everyday and ordinary—for instance, simply not listening when someone speaks. Contempt is also the cause of feeling that just because we may seem different from a person of another race, we are better, and therefore can do as we please with that person.

It was the accumulation of everyday contempt that had young men feel they had the right to shoot other people. It is a national emergency that the fight between contempt and respect be studied, talked of in homes, and seen as a priority in government offices.

Early Boredom, Early Anger

By the time I was 16, I felt that if I lived another 20 years on this planet it would be long enough. I did not see the world as exciting, so I had to make it exciting by stealing cars, racing motorcycles, taking drugs. When I met Aesthetic Realism at age 24, I began to learn that the world as I saw it was very different from the way the world is. I was amazed to learn that the world has a logical structure which, when known, can honestly, with all the facts present, be liked.

When I first read this principle stated by Eli Siegel, “The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites,” I thought, if this is true, this is the greatest discovery of mankind. Now, years later, I am sure it is true, and I am glad I am alive to study this philosophy and teach it to others.

Contempt versus Liking the World

In an Aesthetic Realism class, Mr. Siegel told me, “Anybody who doesn’t think that contempt is a continuous study, living study, and doesn’t want to know all about it, is a person who wants to be hurt and miserable.”

Young people are in anguish because they feel they are in a world that they cannot like. Part of the reason for this feeling is an unjust economic system. Yet, I learned from Aesthetic Realism, we have a choice about how to use what we meet: either to know, and to fight for justice; or to see the world as a contemptible place, a fraud. The second is easier and more popular, but makes a young man dangerous to others and to himself. What this does to a person was described in a class by Mr. Siegel: “For anyone to say, ‘I’m not interested and don’t intend to be interested’—that person is making for himself a private graveyard even while he’s alive.”

Aesthetic Realism Consultations

Studying Aesthetic Realism, my way of seeing the world changed. I once hated books, thought all people were phonies, and thought art was off the mainstream of life. The very things I saw as meaningless (literature, art), I came to see were the things that could answer the deepest questions of my life.

I tell now of the consultations of a young man I’ll call Don Morgan, a 16-year-old high school junior. He had come to feel the world was not worthy of his interest. He said in one consultation, “Lately I feel like I haven’t been doing anything, like I haven’t been going out, and I don’t know why.”

Many young men make themselves important by seeing the world as a mess, a domestic mess, an economic mess, a political mess; they can see things as ugly, dirty, bad smelling, ill-proportioned. Wars continue; death and terror are staple items in every newscast or TV drama.

A young man decides the world is meaningless and he has a right to get back at it through contempt and anger. One result is always that he’s depressed or against himself in some way.

His Aesthetic Realism consultants asked Don Morgan, “It’s not a good thing to feel bored, but in your mind is the pain of boredom better than the pain of getting mixed up with humanity?” He answered, “I don’t know.”

Consultants. The conflict you have—and other people have it too—is, can people really add to you or do they take away from you? For instance, do you think someone who lived 300 years ago could add to you?

Don Morgan. In what way?

Consultants. Make you more yourself. Would you be glad if that could happen?

DM. Yeah, sure.

Consultants. So we should enlist the aid of this person who lived 300 years ago. His name is Rembrandt. Do you know his work?

DM. Not really.

Consultants. Are you interested?

DM. Yeah. I guess so. I’m not sure.

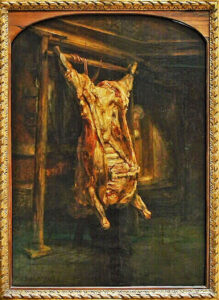

We looked at Rembrandt’s The Slaughtered Ox and asked Don Morgan to describe it. He said, “A dead ox hanging up on a pole, held up by ropes. The colors are different: red, black, light brown.” We asked, “Do you think this made for an emotion in Rembrandt? There could have been a lot of pretty things he might have painted. Do you think there is anything beautiful about this painting?”

Don Morgan answered, “Yes. The way he presents it. It looks light.”

We wanted Don Morgan to see that the world around him, however messy and senseless it might seem, had form. We were teaching him the Aesthetic Realism principle “The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites.”

In Aesthetic Realism: We Have Been There, artist Dorothy Koppelman writes about The Slaughtered Ox. She describes how it makes a one of opposites, opposites that can trouble young people so much—assertion and retreat; what’s awkward, ugly, and what’s proud and bright:

The permanent opposites of the world are here in the thrusting forward of the dead ox and the hidden figure of a woman. Assertion and retreat are motions of reality and they are in us. . . . The painful, lumbering, awkward quality of the slaughtered ox is redeemed by the pride with which it is lifted and put forward into the light.

Among the many questions we asked Don Morgan were these: “Did you betray something narrow in yourself when you found this painting interesting?”

DM. Yes.

Consultants. But was finding it interesting a defeat or victory for you?

DM. A victory. I felt happier looking at the picture.

Consultants. Is there anything in the world that could not add to you? Tomorrow when you are home you are going to have to make a choice: Don Morgan plus world or Don Morgan minus world. The more that is added to you, do you feel heavier or lighter?

DM. Lighter.

Don Morgan has told us that he felt different from that consultation on. He no longer sits hour after hour staring into the television. He has joined the baseball team. He has become much more interested in people—and he is interested in what is occurring in the world.

Aesthetic Realism is the means of changing boredom and anger, by changing one’s state of mind from contempt to respect.

The Education Humanity Is Looking For

The Aesthetic Realism Foundation presents a curriculum of magnificent classes, all based on that central principle Robert Murphy spoke of: “The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites.” There are classes in poetry, anthropology, the visual arts, music, film, marriage, and on the great Aesthetic Realism Teaching Method. These have all been conducted via video conference during the pandemic—and thanks to electronics, people across America and beyond are able to attend those thrilling classes.

There are Aesthetic Realism consultations—an example of which you saw in the Robert Murphy article. Consultations take place now via video conference too, and I’ll be saying more about them. They have the wide, deep, logical understanding of oneself that people thirst for.

Onsite aspects of the Aesthetic Realism Foundation’s beautiful work, necessarily suspended during the pandemic, will be resuming in various ways. There have been the wonderful public seminars on the subjects that affect people most, with such titles as:

- The Debate in Everyone: Should I Feel More or Less?

- The Mix-up in Marriage about Coldness & Warmth

- The Aesthetic Realism Teaching Method: Students Learn, Prejudice Is Defeated!

And there are the dramatic and musical presentations by the Aesthetic Realism Theatre Company.

You can find out more in our Mission Statement—where you will see a description of the Aesthetic Realism Foundation’s Outreach Program. Those loved outreach events have been taking place—via video conference—in these months, at the request of libraries, educational institutions, and community centers.

Then, there is the Foundation’s international periodical. I’ll quote my colleague Aesthetic Realism consultant Barbara Allen on the subject, and I agree with her wholeheartedly:

“Every two weeks a new issue of the international periodical The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known is published. Its editor is Ellen Reiss, Aesthetic Realism Chair of Education. Each issue is, in my opinion, a masterpiece. Ms. Reiss’s commentaries look at and make clear matters that are explained at their source only by Aesthetic Realism — whether the cause of boredom, or what a child is looking for, or the injustice in America now. Her imagination is fresh, her scholarship warm, with every issue.

“TRO presents in serial form lectures by Eli Siegel that are cultural, immediate, and, with enormous diversity, embody his grandeur for history and right now. TRO often contains, too, portions of papers presented at seminars by Aesthetic Realism consultants and associates. This periodical is encyclopedic in the subjects it tells the truth about, to the life-changing benefit of everyone who reads it.”

I Learned This

I’m glad to tell you now some of what I—as a representative person—learned from Aesthetic Realism. Through what I learned, my life changed profoundly, in ways I’d hoped for but hadn’t thought possible. For example, there is the subject of love.

People everywhere long for love. But what real love is, and what in us interferes with our having it, was not understood before Aesthetic Realism. “The purpose of love,” Eli Siegel explained in his book Self and World, “is to feel closely one with things as a whole.”

When I began to study Aesthetic Realism, I didn’t know that how I saw the world had anything to do with how I saw a man. Without putting it into words, I felt that love should be an offset to a world that mixed me up, didn’t appreciate me, got in my way. Unknowingly, I saw love as a means of conquering the world and managing it. I certainly did not feel love was a means of valuing the world through a person—who represents reality.

What I wanted was to have a big effect on men through how I looked—and to have a man make a lot of me, give me praise and make me the most important person in his life. Yet, though I sometimes seemed to get those things, every relationship I had failed.

Then, in one of my first Aesthetic Realism consultations, I began to understand why. I told my consultants I’d become interested in a man at my job—but I spoke with a huge lack of clarity about what in him affected me. They asked me with humor, “Are you very taken by how taken he is by you?” And they asked me this surprising yet deep question: “Do you see Mr. Carter as wholly existing?” I didn’t—because I didn’t see him as having a whole life, with ever so many thoughts and feelings. I was just interested in his liking me.

Ellen Reiss, who was one of my consultants, asked, “Do you think you’re afraid of the insides of people?” I said “Yes.” I remembered sitting across a table from a man with whom I was in a relationship when I lived in Montana—and not asking him anything about himself. Ms. Reiss explained, “There is a whole aspect of a person that you don’t recognize as real.”

Meryl Nietsch. What is that?

Ellen Reiss. It’s the inner life of the person. It’s the wholeness of a person’s feelings. It’s the world in a person. And people in the history of amour have loved shells of other people because they’re terrified of all the dimensions of a person.

This was a turning point in my life. It was the beginning of my wanting to see men, and people as such, as real, as having questions as deep as my own, as having reality in them. And reality in a person means, centrally, that the opposites which are in the whole world and in art are in a person too, and the person longs to make them one: such opposites as sureness and unsureness; strength and gentleness; high and low, or pride and humility. I was learning to see a person, including a man, with respect instead of contempt.

Here I’ll say too that what I’m describing is not only the basis for love but the basis for justice. When you see that another person has the structure of the world itself—the opposites—in him or her, you don’t want to hurt that person.

I am grateful without bounds for what I learned that made possible my tremendously happy marriage to Bennett Cooperman, an Aesthetic Realism consultant, and singer and actor with the Aesthetic Realism Theatre Company. When I first met Bennett, I respected him very much. I was affected by a relation of logic and feeling in him: his intellectual perceptions about the world, drama, music—and his warmth toward people. Because of my study of Aesthetic Realism, I now had a desire to know a man, including how he himself wanted to be better. And Bennett also wanted to understand me. He has been a deep friend. Studying in the magnificent professional classes for consultants and associates, taught by Ellen Reiss, we are getting the richest education about the world and ourselves!

Food, & the World It Comes From

Before I began to study Aesthetic Realism, I had the eating disorders bulimia and anorexia. I felt tormented by them, but hid my torment under a sunny manner. I have spoken publicly and written articles about what I learned from Aesthetic Realism about these disorders. For now, I can tell you that eating disorders arise from a way of seeing the whole world. In Self and World, Eli Siegel writes in beautiful prose:

The taking of food is more than nutrition alone; it is also a profound homage of the self to its surroundings. We are saying when we eat, and with humility, too, that we need the world from which our food comes. We say, unconsciously, when we eat well: Bless reality which gives us our daily nutriment.—If we can’t logically bless, our daily bread will be a daily peril.

My “daily bread” was a “daily peril.” Then, in Aesthetic Realism consultations, I heard deep, compassionate criticism of my contempt for the world; and my desire to know, like, and respect the world was encouraged. I learned that, as my consultants put it,

[bulimia] is a way of managing the world — having it please you but not affect you deeply. Anorexia is a means of having yourself pure, without any additions.

What I learned from Aesthetic Realism enabled ten years of the agony of eating disorders to end. Today I eat with a dignity and self-respect for which I’m very grateful.

I have seen, through careful looking, that Eli Siegel is the philosopher who understood the human mind.

A Mother, a Daughter, & Reality

Growing up and later, the person about whom I had the most difficulty was my mother, Marion Nietsch. We argued a lot. I told myself she was always trying to manage me. But I was also mean to her, wanting to prove that nothing she did could make me happy. I remember how once she bought me a lovely summer blouse, for which I showed such disdain. I will never forget the look on her face, how hurt she was.

In an Aesthetic Realism consultation, when my consultants asked me about my mother, I said, “I try to forget about her.” They asked, “Do you think you’re mad at her because you can’t just sum her up?” This was true. I remembered seeing, when I was a child, a generosity in her as she wanted people in our neighborhood to fare well. Often she would invite someone to our home who was alone during a holiday, or give money to a relative who needed it. And this was the same mother who could be so severe. I didn’t know that both Marion Nietsch and I were longing to make sense of opposites in ourselves—like sweetness and severity.

My consultants asked, “If you don’t want to understand your mother, will it be hard for you to understand any other person?” Looking at her newly, I thought of how she had a difficult time with our large family, raising five boys and me. Money was tight, and we did not make it easy for her. Like many parents today, my mother and father struggled in an economy that is based not on good will for people but on using people for profit.

Through my Aesthetic Realism consultations, I began to see who my mother was. My consultants asked, “Do you think you really have a sense of what a woman with six children feels?” I didn’t. “But,” they continued, “can mind try to know what that feels like?” “I think so,” I said. “Do you think since you were the first child, she should have just stopped there?”—the question was asked with humor, but I did feel that!

I was given an assignment to write a soliloquy of Marion Nietsch when she was a young woman. And writing it, I realized there was so much I didn’t know about her.

As my study continued, I did something very different from once: I had conversations with my mother about her life. Often, they took place as we sat together by Long Island’s Great South Bay. There were many conversations, and they were exciting. She told me that she sang in a band, that she was valedictorian of her eighth grade class, and that one of her favorite novels as a girl was Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. I learned about what she felt living in Brooklyn, and later moving to then-rural Seaford, Long Island, and about meeting my father, Richard Nietsch. I was seeing her with new eyes: she was not just my mother but a person who had to do with so much. She was one and many, personal and impersonal, familiar and mysterious. Seeing reality’s opposites in her, I was liking, deeply and stirringly, both Marion Nietsch and the world itself.

My mother died some years ago, and I will always cherish the friendship between us that came to be because of Aesthetic Realism. She herself was very grateful for what she called in a letter “the kind work of Eli Siegel.”

That kind education, with its logic and comprehension, is needed today more than ever!

Sincerely,

![]()

Meryl Nietsch-Cooperman

Aesthetic Realism Consultant